11 Crops Oregon Homeowners Aren’t Allowed To Grow In Their Backyards

Most people assume that if you own your home, you can grow whatever you want in your backyard. After all, it’s your space, your soil, and your time.

But in Oregon, that’s not always how it works. Some plants and crops are restricted or outright banned, even for homeowners who just want to grow a little food or try something new.

This can be surprising, especially if you’ve ever planted seeds without thinking twice about the rules. You might be doing everything with good intentions and still end up breaking a local or state regulation.

And let’s be honest, nobody wants a fine or a warning letter over a garden project.

Knowing what’s allowed ahead of time can save you a lot of frustration. It also helps protect local ecosystems, prevent invasive species, and keep neighborhoods safe and healthy.

That’s something most gardeners can appreciate, even if the rules feel a little confusing at first.

If you’ve ever wondered whether certain crops are off-limits, or if you’ve heard rumors but never knew what was true, you’re not alone. Many Oregon homeowners are surprised by what’s on the restricted list.

1. African Rue (Peganum harmala)

You might stumble across this plant while browsing for drought-tolerant perennials or medicinal herbs online. It looks innocent enough, bushy green foliage topped with cheerful yellow flowers that seem perfect for a low-water garden bed.

Some seed sellers market it as a hardy ornamental or even as a spiritual plant with historical uses in traditional medicine.

But here’s the catch: Oregon classifies African Rue as a prohibited noxious weed, meaning you can’t legally plant, grow, sell, or transport it anywhere in the state.

Why the ban? This plant spreads aggressively and thrives in disturbed soils, roadsides, and rangelands.

Once established, it outcompetes native vegetation and can poison livestock that graze on it. Its deep taproot makes removal incredibly difficult, and seeds remain viable in soil for years.

African Rue has already invaded parts of the western U.S., and Oregon wants to prevent it from gaining a foothold here.

If you’re drawn to yellow-flowering perennials, try Oregon grape or goldenrod instead, both are native, wildlife-friendly, and completely legal.

Always double-check seed sources and avoid importing plants from unregulated online marketplaces.

If you accidentally receive African Rue seeds or spot the plant growing wild, contact your local Oregon Department of Agriculture office or county weed control program for safe removal guidance.

2. Camelthorn (Alhagi pseudalhagi)

Picture a thorny shrub that looks like it belongs in a desert landscape, dense, spiny, and tough as nails. Camelthorn might catch your eye if you’re searching for xeriscaping ideas or unique drought-resistant plants to fill a hot, dry corner of your yard.

Some gardeners even see it advertised as a forage plant for livestock or a novelty addition to arid-themed gardens. But don’t be fooled: this plant is a serious agricultural nightmare and is completely banned in Oregon.

Camelthorn earned its spot on Oregon’s prohibited noxious weed list because it spreads like wildfire through underground rhizomes and seeds.

It invades pastures, hayfields, and irrigation ditches, forming impenetrable thickets that choke out crops and native plants.

The sharp thorns make manual removal painful and dangerous, and its deep root system can extend over 20 feet into the ground. Livestock won’t graze near it, and it can quickly ruin productive farmland.

If you need a tough, spiny plant for your landscape, consider native Oregon shrubs like ocean spray or osoberry. These provide structure, support local wildlife, and won’t turn your backyard into an invasive danger zone.

Camelthorn seeds sometimes arrive mixed in with imported plant material, so always buy from reputable Oregon nurseries. If you suspect you have Camelthorn, report it immediately, early detection is key to stopping its spread.

3. Cape-Ivy (Delairea odorata)

Scrolling through Pinterest or Instagram gardening pages, you might see a cascading vine covered in cheerful yellow daisy-like flowers.

Cape-Ivy looks like the perfect groundcover or trailing plant for shaded fences and garden walls.

It grows fast, stays green year-round, and seems like a dream plant for filling empty spaces. But this attractive vine is banned in Oregon because it’s one of the most aggressive invasive plants threatening our native forests and riparian areas.

Cape-Ivy smothers everything in its path. It climbs trees, blankets shrubs, and forms dense mats that block sunlight from reaching native plants below.

This causes entire ecosystems to collapse as native vegetation withers off and wildlife loses critical habitat and food sources. The vine spreads through stem fragments, meaning even a tiny piece left behind can regrow into a new infestation.

It thrives in Oregon’s mild, wet climate and has already invaded parts of the Pacific Northwest.

For a beautiful, legal groundcover alternative, try native wild ginger, inside-out flower, or sword fern. These plants support local pollinators and wildlife while staying well-behaved in your garden.

Never accept Cape-Ivy cuttings from friends or plant swaps, and always inspect nursery plants carefully.

If you find Cape-Ivy growing on your property, remove it carefully, bag all plant material and dispose of it in the trash, not your compost pile.

4. Coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara)

Early spring gardeners love the idea of cheerful yellow blooms popping up before most other plants wake up. Coltsfoot fits that bill perfectly, bright yellow dandelion-like flowers appear in late winter, followed by large hoof-shaped leaves.

You might see it sold in herbal remedy catalogs or advertised as a traditional medicinal plant for coughs and respiratory issues. It seems harmless, even charming.

But Oregon has placed Coltsfoot on the noxious weed list because it’s an aggressive spreader that disrupts natural habitats.

Coltsfoot spreads through both seeds and underground rhizomes, allowing it to colonize disturbed soils, roadsides, and streambanks quickly.

Once established, it forms dense colonies that crowd out native wildflowers and early-season plants that pollinators depend on.

Its rhizomes are incredibly persistent, making eradication nearly impossible without diligent, long-term effort. Coltsfoot has also been linked to liver toxicity in humans, so using it as an herbal remedy carries serious health risks.

For early-season color, plant native Oregon sunshine like glacier lilies, trillium, or Oregon grape. These provide critical early nectar sources for bees and butterflies without the invasive risk.

Avoid buying Coltsfoot from online herbal suppliers or international seed companies. If you discover it growing in your yard, dig it out carefully, removing as much root material as possible, and monitor the area for regrowth.

Contact your county weed board for professional removal advice if needed.

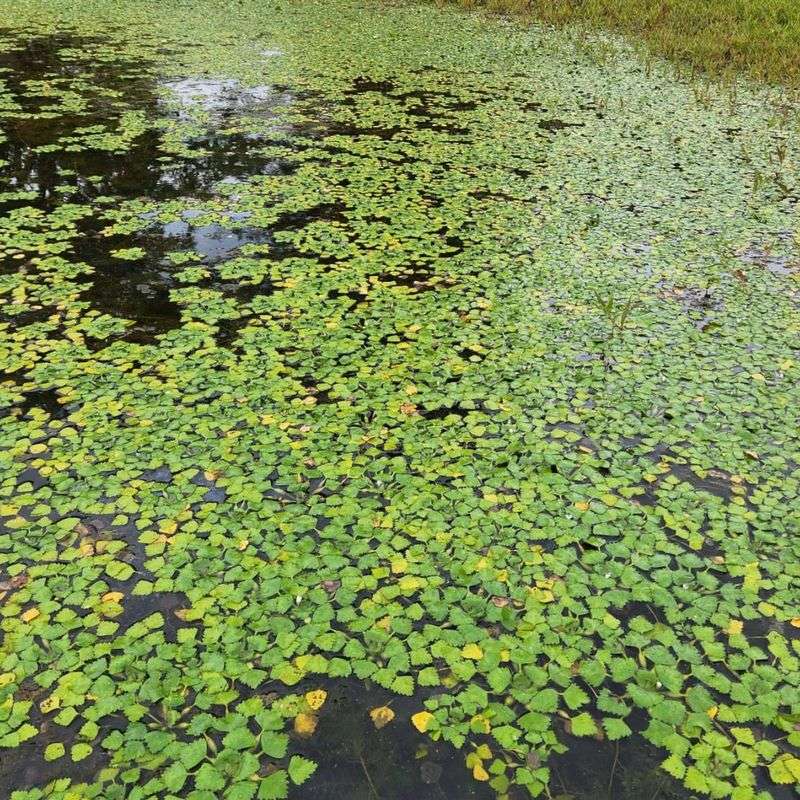

5. Common Frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae)

Water gardeners and pond enthusiasts often search for floating plants to add visual interest and shade to backyard ponds.

Common Frogbit looks like a miniature water lily with round, glossy leaves and delicate white flowers.

It’s often sold online as an easy-care aquatic plant that helps control algae and provides shelter for fish. It seems like the perfect addition to a tranquil water feature.

But Oregon has banned Common Frogbit because it’s a devastating invasive species that destroys aquatic ecosystems.

Common Frogbit reproduces rapidly, forming thick floating mats that cover entire water surfaces. These mats block sunlight from reaching underwater plants, causing them to wither and depleting oxygen levels in the water.

Fish, amphibians, and native aquatic insects suffer as their habitat collapses. The plant spreads through fragments, meaning even a tiny piece can hitchhike on boots, fishing gear, or pet birds and start new infestations.

It’s already invaded waterways in other states, and Oregon is working hard to keep it out.

For a safe, legal floating plant, try native duckweed in moderation or water lilies from reputable Oregon pond suppliers.

Always inspect new aquatic plants carefully before adding them to your pond, and never release pond water or plants into natural waterways.

If you suspect you’ve accidentally introduced Common Frogbit, contact the Oregon Department of Agriculture immediately. Early detection and rapid response are critical to preventing widespread damage to Oregon’s lakes, rivers, and wetlands.

6. European Water Chestnut (Trapa natans)

Backyard pond owners sometimes come across European Water Chestnut while searching for ornamental aquatic plants with interesting foliage. This floating plant features rosettes of triangular leaves and produces unusual spiny seed pods that look almost prehistoric.

Some gardeners find the seeds fascinating and order them online out of curiosity or for educational purposes.

But this plant is strictly prohibited in Oregon because it’s one of the most destructive invasive aquatic species in North America.

European Water Chestnut grows explosively, forming dense mats that can cover acres of water in a single growing season. These mats block sunlight, destroy underwater vegetation, and create stagnant conditions that harm fish and wildlife.

The spiny seeds are sharp enough to pierce shoes and feet, making infested waters dangerous for swimmers and waders.

Each plant can produce up to 20 seeds that remain viable in sediment for over a decade, making eradication extremely difficult once established.

If you want texture and interest in your pond, stick with native plants like water smartweed or pondweed varieties available from Oregon aquatic plant nurseries. Never purchase aquatic plants from unregulated online sellers or international sources.

Always inspect and quarantine new pond plants before introducing them to your water feature. If you discover European Water Chestnut, do not attempt removal yourself, contact your local invasive species coordinator immediately.

This plant requires professional management to prevent accidental spread.

7. Flowering Rush (Butomus umbellatus)

Imagine a tall, elegant plant with grass-like leaves and clusters of pink flowers rising above the water on sturdy stems. Flowering Rush looks absolutely stunning in water gardens and pond edges, which is why it’s sometimes sold as an ornamental aquatic plant.

Gardeners love its height and showy blooms, and it seems like a natural fit for wetland-style landscaping.

But Oregon has banned Flowering Rush because it aggressively invades wetlands, ditches, and slow-moving waterways, causing serious ecological and economic damage.

Flowering Rush spreads through both seeds and underground bulbils, allowing it to colonize new areas rapidly. It forms dense stands that crowd out native wetland plants, reducing habitat quality for waterfowl, fish, and amphibians.

The thick root systems clog irrigation ditches and drainage canals, creating costly problems for farmers and water managers. Once established, Flowering Rush is incredibly difficult to control because fragments of roots and bulbils can regenerate into new plants.

For beautiful vertical interest in wet areas, try native plants like Pacific iris, rushes, or sedges. These provide the same structural appeal while supporting Oregon’s native wildlife and pollinators.

Never buy aquatic plants from sellers who don’t clearly label their stock or source plants from outside Oregon. If you spot Flowering Rush in natural waterways or your property, report it to your county weed control office right away.

Early detection makes a huge difference in preventing widespread infestation.

8. Garden Yellow Loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris)

Browsing through perennial plant catalogs, you might be drawn to a tall, cheerful plant covered in spikes of bright yellow flowers.

Garden Yellow Loosestrife looks like a perfect addition to cottage gardens or naturalized areas, and it’s often marketed as a low-maintenance perennial that attracts pollinators.

Some gardeners even receive it as a pass-along plant from well-meaning neighbors. But Oregon restricts this plant because it’s an aggressive spreader that invades wetlands, ditches, and riparian areas, displacing native vegetation.

Garden Yellow Loosestrife spreads through both seeds and rhizomes, forming dense colonies that outcompete native plants. It thrives in wet soils and can quickly take over pond edges, stream banks, and low-lying garden areas.

Once established, it’s difficult to remove because the rhizomes persist underground and regrow even after repeated cutting. The plant provides little value to native wildlife compared to the diverse native plants it replaces, disrupting local ecosystems.

For similar yellow blooms that won’t cause problems, try native plants like Oregon sunshine, Pacific stonecrop, or goldenrod. These support local bees, butterflies, and beneficial insects while staying well-behaved in your garden.

Always research plants before accepting them from plant swaps or friends, and avoid buying from sellers who don’t clearly identify their stock.

If you discover Garden Yellow Loosestrife on your property, dig it out carefully, removing all rhizome fragments, and dispose of plant material in the trash.

Monitor the area regularly for regrowth and stay vigilant.

9. Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)

Few plants generate as much alarm as Giant Hogweed, and for good reason. This towering plant can reach 15 feet tall with massive umbrella-like white flower clusters and huge, deeply lobed leaves.

Some gardeners mistakenly think it’s an impressive ornamental or confuse it with native cow parsnip. Others encounter it in wild areas or inherited gardens without realizing the danger.

Giant Hogweed is strictly prohibited in Oregon because its sap contains toxic chemicals that cause severe, painful burns and long-lasting skin damage.

Contact with Giant Hogweed sap, combined with sunlight, causes phytophotodermatitis, a chemical reaction that produces painful blisters, scarring, and sensitivity that can last for years. Even brushing against the plant can transfer sap to your skin.

Beyond the health risks, Giant Hogweed is also an aggressive invader that crowds out native plants along streams, roadsides, and forest edges. Its seeds spread easily through water and soil movement, and the plant can rapidly colonize new areas.

If you want dramatic height and structure, try native plants like thimbleberry, elderberry, or oceanspray. These provide visual impact without the danger or invasive behavior.

Never touch or attempt to remove Giant Hogweed yourself, wear full protective gear or hire professionals. If you spot it, photograph it from a safe distance and report it to the Oregon Department of Agriculture immediately.

Do not let children or pets near the plant, and warn neighbors if you discover it nearby.

10. Goatgrass (Aegilops species)

Most homeowners would never intentionally plant Goatgrass, but it sometimes shows up accidentally in wildflower seed mixes, imported grain, or contaminated soil. This grass looks similar to wheat and other cereal crops, which is exactly the problem.

Goatgrass is a serious agricultural threat and is prohibited in Oregon because it hybridizes with wheat, contaminates grain harvests, and reduces crop yields.

It might seem harmless in a backyard setting, but its presence poses a direct threat to Oregon’s important wheat-growing regions.

Goatgrass spreads through seeds that easily mix with wheat and other grains, making it difficult to detect until it’s too late. Once established in agricultural fields, it reduces crop quality, lowers market value, and can result in entire harvests being rejected.

The seeds are sharp and can injure livestock, and the plant provides little forage value. Even small infestations in residential areas can spread to nearby farms through wind, wildlife, or contaminated equipment.

If you’re planting wildflower meadows or native grasses, buy only from certified Oregon seed suppliers who guarantee weed-free stock. Avoid bulk seed mixes from unknown sources or international sellers.

If you notice an unfamiliar grass that resembles wheat growing in your yard, take a photo and contact your local extension office or county weed control for identification.

If it’s Goatgrass, remove it immediately before it goes to seed, bag all plant material, and dispose of it properly.

Protecting Oregon’s agricultural industry starts in your own backyard.

11. Dense-Flowered Cordgrass (Spartina densiflora)

Coastal property owners sometimes search for salt-tolerant grasses to stabilize shorelines or create natural-looking buffers along estuaries and tidal areas.

Dense-Flowered Cordgrass might seem like a practical choice, it’s tough, grows in salty conditions, and forms dense stands.

Some gardeners even see it recommended in outdated landscaping guides or online forums.

But Oregon has banned this plant because it’s a highly invasive species that destroys critical estuarine habitats and threatens native salt marsh ecosystems.

Dense-Flowered Cordgrass spreads aggressively through rhizomes and seeds, forming monocultures that replace diverse native salt marsh plants.

These monocultures alter sediment patterns, change water flow, and eliminate habitat for shorebirds, juvenile fish, and invertebrates that depend on healthy estuaries.

The plant also hybridizes with native cordgrass species, weakening their genetic integrity and further disrupting ecosystems. Once established, Dense-Flowered Cordgrass is extremely difficult and expensive to remove.

For coastal landscaping, work with native plant specialists to select appropriate Oregon salt marsh species like tufted hairgrass, seaside arrowgrass, or Pacific silverweed. These plants support local wildlife, stabilize shorelines naturally, and won’t cause ecological harm.

Never transplant grasses from other regions or accept plants from unknown sources. If you live near the coast and spot unfamiliar cordgrass, report it to the Oregon Department of Agriculture or your local Soil and Water Conservation District.

Protecting Oregon’s estuaries requires vigilance and responsible plant choices from everyone.