14 Crops Colorado Homeowners Are Not Allowed To Grow In Their Yards

Colorado’s dramatic landscapes support an incredible range of plant life, but not every plant belongs in the backyard.

In fact, the state maintains strict rules on certain species that threaten ecosystems, farmland, water systems, or public health.

These plants—classified as prohibited noxious weeds—cannot be grown, sold, or allowed to spread, even unintentionally.

Some were once introduced as ornamentals, while others slipped in through contaminated feed, seed, or soil.

Over time, they proved incredibly destructive, outcompeting native vegetation and causing costly damage.

Many homeowners don’t realize that these plants are illegal until they receive a warning from their county weed authority.

Understanding which species appear on Colorado’s banned list can help prevent violations and protect local environments.

Whether you’re gardening for beauty, food, or wildlife habitat, steering clear of these prohibited crops ensures your landscape remains safe, legal, and environmentally responsible.

1. Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum Salicaria)

Purple loosestrife might look gorgeous with its tall purple flower spikes, but this European import has become one of Colorado’s most destructive wetland invaders.

Originally brought to North America as an ornamental garden plant in the early 1800s, it quickly escaped cultivation and now threatens native wetland ecosystems across the state.

A single mature plant can produce up to 2.7 million seeds per year, which spread easily by water, wind, and wildlife.

These seeds remain viable in soil for many years, making eradication incredibly challenging once the plant establishes itself.

Colorado law strictly prohibits planting, selling, or transporting purple loosestrife anywhere in the state.

The plant forms dense stands that choke out native cattails, sedges, and rushes that provide essential habitat for waterfowl and other wildlife.

Wetlands dominated by purple loosestrife offer poor food sources for native animals and disrupt the natural water flow patterns.

If you spot this plant near water on your property, contact your local county extension office immediately for guidance on proper removal.

Homeowners caught growing purple loosestrife can face significant fines and may be required to pay for professional eradication services.

Native alternatives like blazing star or Rocky Mountain penstemon offer beautiful purple blooms without the ecological damage.

2. Yellow Starthistle (Centaurea Solstitialis)

Bright yellow flowers might seem cheerful, but yellow starthistle poses a severe threat to horses and other grazing animals throughout Colorado.

This Mediterranean native produces a neurotoxin that causes a condition called chewing disease in horses, leading to brain damage and an inability to eat or drink properly.

Once symptoms appear, the damage is permanent and progressive.

The plant thrives in disturbed soils, roadsides, and overgrazed pastures, spreading rapidly through Colorado’s drier regions.

Each plant produces between 10,000 and 75,000 seeds that can remain dormant in soil for up to ten years.

Colorado classifies yellow starthistle as a List A noxious weed, meaning property owners must report and eradicate it immediately upon discovery.

The sharp spines on its flower heads make hand-pulling painful, so proper protective equipment is essential during removal.

Landowners who fail to control yellow starthistle on their property can face legal action and be held responsible for eradication costs.

The plant also outcompetes native wildflowers and grasses, reducing biodiversity and forage quality.

Early detection is critical because small infestations are much easier to manage than established populations.

If you think you’ve spotted yellow starthistle, take photos and contact your county weed management office before attempting removal to ensure proper identification and disposal.

3. Giant Hogweed (Heracleum Mantegazzianum)

Few plants are as dangerous as giant hogweed, a towering invasive that can reach heights of fifteen feet or more.

The sap from this plant contains toxic compounds called furanocoumarins that cause severe phototoxic reactions when exposed to sunlight.

Even brief contact with the sap followed by sun exposure can result in painful blisters, permanent scarring, and long-lasting sensitivity to light.

If the sap gets in your eyes, it can cause temporary or even permanent blindness.

Giant hogweed resembles a supersized version of Queen Anne’s lace, with massive white flower clusters that can span two feet across.

Colorado has banned this plant entirely, and any sightings must be reported to state agricultural authorities immediately.

Children are especially vulnerable because they might be attracted to the plant’s hollow stems, which kids historically used as peashooters or telescopes in the plant’s native range.

Never attempt to remove giant hogweed yourself without proper protective clothing, including gloves, long sleeves, and eye protection.

Professional removal is strongly recommended because even dead plant material can retain toxic sap for some time.

The plant spreads through seeds, with each plant producing up to 20,000 seeds that remain viable for several years.

Fortunately, giant hogweed is relatively rare in Colorado, but vigilance is essential to prevent its establishment.

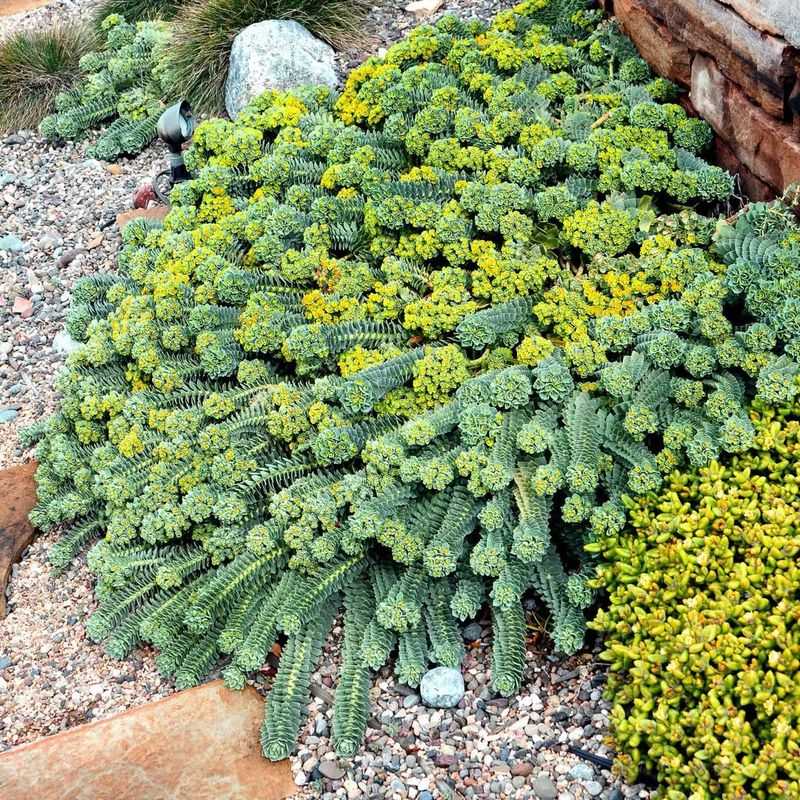

4. Myrtle Spurge (Euphorbia Myrsinites)

Garden centers once sold myrtle spurge as an attractive drought-tolerant ground cover, but Colorado now prohibits its sale and cultivation.

This Mediterranean native features beautiful blue-green succulent leaves arranged in spiral patterns along trailing stems, topped with chartreuse yellow flower clusters.

Many homeowners planted it for its ability to thrive in poor soils and its supposed resistance to deer browsing.

The problem is that myrtle spurge escapes gardens easily and invades natural areas, where it outcompetes native plants.

All parts of the plant contain a milky white sap that causes skin irritation, blistering, and temporary blindness if it contacts eyes.

Pets that chew on myrtle spurge can experience severe mouth pain, drooling, and digestive upset.

The plant spreads both by seed and vegetatively, with stems rooting wherever they touch the ground.

Seeds are dispersed explosively when the seed capsules mature, shooting seeds several feet from the parent plant.

Colorado reclassified myrtle spurge as a List A noxious weed, requiring mandatory eradication from all properties.

Homeowners who still have myrtle spurge from before the ban must remove it completely, including all root fragments.

Wear protective gloves and eyewear during removal, and dispose of plant material in sealed bags in the trash, never in compost piles.

Native alternatives like pussytoes or stonecrop provide similar ground-covering benefits without the invasive tendencies.

5. Russian Knapweed (Acroptilon Repens)

Russian knapweed arrived in North America as a contaminant in alfalfa seed shipments over a century ago and has plagued Colorado ever since.

This aggressive perennial develops an extensive root system that can penetrate soil to depths of twenty feet or more, making eradication extremely difficult.

The plant produces chemicals that inhibit the growth of surrounding vegetation, essentially poisoning the soil for other plants.

Russian knapweed forms dense colonies that choke out desirable grasses, garden vegetables, and native wildflowers.

Its gray-green foliage and purple thistle-like flowers might appear innocuous, but a single plant can spread vegetatively to cover large areas within just a few seasons.

Colorado lists Russian knapweed as a List B noxious weed, requiring management plans to prevent its spread.

The plant is also toxic to horses, causing a neurological condition similar to what yellow starthistle produces.

Affected horses lose coordination and the ability to eat properly, with no effective treatment available.

Controlling Russian knapweed requires a long-term commitment because root fragments left in soil will resprout.

Mowing doesn’t work because the plant simply regrows from its deep roots.

Effective management typically involves a combination of properly timed herbicide applications and competitive planting with desirable species.

If you discover Russian knapweed on your property, consult with your county weed coordinator to develop an appropriate control strategy.

6. Leafy Spurge (Euphorbia Esula)

Leafy spurge ranks among Colorado’s most economically damaging invasive plants, costing ranchers and landowners millions annually in lost forage and control efforts.

This European perennial produces distinctive yellow-green bracts that many people mistake for flowers, appearing in spring and early summer.

What makes leafy spurge so problematic is its incredibly persistent root system that extends both deep and wide underground.

Vertical roots can reach fifteen feet deep, while horizontal roots spread outward, sending up new shoots that form dense patches.

Even tiny root fragments left in soil after removal attempts will generate new plants.

The plant contains caustic milky sap that irritates skin and mucous membranes in humans and animals alike.

Cattle and horses avoid grazing in areas infested with leafy spurge, reducing usable pasture significantly.

Colorado law designates leafy spurge as a List B species, requiring property owners to prevent seed production and implement management strategies.

The plant produces seeds in three-chambered capsules that explode when ripe, launching seeds up to fifteen feet away.

Seeds can remain viable in soil for at least eight years, creating a persistent seed bank.

Biological control using specialized flea beetles has shown some success, but eradication remains challenging.

Homeowners should never purchase property without checking for leafy spurge because established infestations can take decades to control and significantly reduce property values.

7. Orange Hawkweed (Hieracium Aurantiacum)

Orange hawkweed might catch your eye with its brilliant orange-red flowers that resemble tiny dandelions, but this European native has no place in Colorado gardens.

The plant spreads aggressively through both seeds and creeping above-ground stems called stolons that root at nodes, similar to how strawberry plants spread.

A single plant can produce numerous stolons that quickly form dense mats, crowding out lawn grasses, native wildflowers, and garden plants.

Each flower head produces dozens of seeds equipped with feathery structures that allow wind dispersal over considerable distances.

Orange hawkweed thrives in the cool mountain climates found throughout much of Colorado, particularly in meadows, lawns, and disturbed areas.

Once established, it creates monoculture patches that provide little value to native pollinators and wildlife compared to native plant communities.

The plant’s shallow, fibrous root system makes hand-pulling seem easy, but any stolon fragments left behind will reestablish quickly.

Colorado classifies orange hawkweed as a List B species, meaning management is required to prevent further spread.

Homeowners who discover orange hawkweed should remove plants before they flower and set seed.

Dig carefully to remove all stolons and roots, checking the area regularly for several years to catch any regrowth.

Maintaining healthy, thick turf or native plant cover is your best defense against orange hawkweed invasion.

Native alternatives like blanket flower or prairie coneflower provide vibrant orange blooms without the invasive behavior.

8. Garlic Mustard (Alliaria Petiolata)

Garlic mustard might seem harmless with its delicate white flowers and edible leaves that smell like garlic when crushed, but this European invader transforms forest ecosystems.

The plant thrives in shaded areas under trees where it forms dense carpets that exclude native spring wildflowers like trilliums and wild ginger.

What makes garlic mustard particularly insidious is its ability to alter soil chemistry through chemicals its roots release.

These compounds disrupt beneficial mycorrhizal fungi that native plants depend on for nutrient uptake, giving garlic mustard a competitive advantage.

The plant completes its life cycle as a biennial, spending its first year as a low rosette of kidney-shaped leaves before sending up flowering stalks in the second year.

Each plant can produce thousands of tiny black seeds that remain viable in soil for at least five years.

Seeds are easily transported on shoes, clothing, and pet fur, helping the plant spread to new locations.

Colorado prohibits growing, selling, or transporting garlic mustard anywhere in the state.

Early spring is the best time for removal, when soil moisture makes pulling easier and plants haven’t yet set seed.

Grasp plants at the base and pull steadily to remove the entire taproot, which resembles a thin white carrot.

Dispose of pulled plants in sealed trash bags, never in compost, because seeds can mature even on removed plants.

Monitor removal sites for several years because the soil seed bank will continue producing new plants.

9. Diffuse Knapweed (Centaurea Diffusa)

Diffuse knapweed transforms from an innocent-looking rosette into a tumbleweed-like seed dispersal machine that can spread thousands of seeds across your property.

This Eurasian biennial or short-lived perennial produces bushy plants with numerous branches tipped with small white to pale purple flowers.

When the plant matures and dries in late summer, the entire above-ground portion breaks off at the base and tumbles across the landscape, scattering seeds wherever it rolls.

Each plant can produce up to 18,000 seeds that remain viable in soil for several years, creating a persistent seed bank.

Diffuse knapweed thrives in disturbed soils, roadsides, and overgrazed areas, but it readily invades well-maintained yards and gardens too.

The plant develops a deep taproot that allows it to access water unavailable to shallow-rooted native plants, giving it an advantage during Colorado’s dry summers.

Colorado law requires property owners to prevent diffuse knapweed from producing seed and to implement control measures.

The plant reduces forage quality in pastures and rangeland, and its spiny flower bracts make hay unpalatable to livestock.

Early detection and removal before seed production is critical for preventing infestations from becoming established.

Hand-pulling works for small populations if you remove the entire taproot, but larger infestations may require herbicide application.

Maintaining healthy plant cover through proper watering and fertilization helps prevent diffuse knapweed from gaining a foothold in your landscape.

Report large infestations to your county weed management office for assistance.

10. Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea Stoebe)

Spotted knapweed earned its name from the distinctive black-tipped bracts beneath its purple flower heads that create a spotted appearance.

This European native has invaded millions of acres across the western United States, displacing native plants and reducing forage for livestock and wildlife.

The plant produces chemicals through its roots that inhibit the growth of neighboring plants, a phenomenon called allelopathy.

These toxic compounds give spotted knapweed an unfair advantage over native species that haven’t evolved defenses against such chemical warfare.

Spotted knapweed typically lives as a biennial or short-lived perennial, forming a ground-hugging rosette in its first year before bolting to produce flowers.

A single mature plant can generate up to 25,000 seeds, and wind, animals, vehicles, and contaminated hay all contribute to seed dispersal.

The plant is also toxic to horses when consumed in large quantities, causing a neurological disorder called nigropallidal encephalomalacia.

Colorado designates spotted knapweed as a List B noxious weed, requiring management to limit its spread.

The plant’s deep taproot makes hand-pulling challenging unless soil is moist, and any root fragments left behind can regenerate.

Biological control agents including several species of seed-feeding flies and root-boring weevils have been released in Colorado with varying success.

For homeowners, maintaining dense, healthy turf or native plant communities is the best prevention strategy.

If spotted knapweed appears in your yard, remove plants before they flower and monitor the area for several years.

11. Houndstongue (Cynoglossum Officinale)

Houndstongue combines the worst traits of invasive plants: it’s toxic to livestock, produces annoying burrs that stick to everything, and spreads rapidly across disturbed landscapes.

This European biennial gets its common name from the shape and texture of its leaves, which supposedly resemble a dog’s tongue.

The plant produces small reddish-purple flowers in its second year, followed by nutlets covered in barbed prickles that attach firmly to fur, feathers, and fabric.

Anyone who has tried to remove houndstongue burrs from a long-haired dog knows how frustrating these sticky seeds can be.

Beyond the nuisance factor, houndstongue contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids that cause irreversible liver damage in cattle, horses, and other grazing animals.

Animals typically avoid eating the plant when fresh because of its unpleasant odor and taste, but dried plants in hay lose their smell while retaining toxicity.

Colorado requires property owners to prevent houndstongue from producing seed and to manage existing populations.

The plant thrives in disturbed areas, roadsides, overgrazed pastures, and even neglected corners of residential yards.

Its thick taproot can extend two feet deep, making removal challenging once plants mature.

The best control strategy is removing plants during the rosette stage in early spring before the taproot becomes too established.

Wear gloves during removal because some people experience skin irritation from contact with the plant’s foliage.

Dispose of seed-bearing plants in sealed bags to prevent burrs from spreading during transport to the trash.

12. Medusahead (Taeniatherum Caput-Medusae)

Medusahead gets its memorable name from seed heads with long, twisted bristles that supposedly resemble the snake-covered head of the mythological Medusa.

This annual grass from Eurasia has become one of the most problematic invasive grasses in the western United States, though Colorado infestations remain relatively limited.

The plant germinates in fall, grows through winter and spring, then sets seed in early summer before dying back.

Medusahead produces dense stands that outcompete native grasses and wildflowers, dramatically reducing plant diversity and wildlife habitat quality.

The long bristles on its seed heads make the dried grass unpalatable to livestock and wildlife, essentially creating biological deserts where it dominates.

High silica content in the plant tissues further reduces its value as forage and makes it difficult for animals to digest.

Medusahead also increases fire risk because its dried biomass creates continuous fine fuel that carries flames rapidly across the landscape.

Colorado classifies medusahead as a List A noxious weed, requiring immediate eradication when discovered.

Early detection is crucial because small infestations can be controlled, while large populations are extremely difficult and expensive to manage.

The plant spreads primarily through seed, with each plant producing numerous seed heads that shatter easily, dropping seeds near the parent plant.

Seeds can also travel on vehicles, equipment, and animals, so cleaning gear after visiting infested areas helps prevent spread.

If you suspect medusahead on your property, contact your county weed coordinator immediately for positive identification and guidance on appropriate control methods.

13. Jointed Goatgrass (Aegilops Cylindrica)

Jointed goatgrass poses a unique threat among Colorado’s prohibited plants because of its ability to hybridize with cultivated wheat crops.

This Mediterranean annual grass looks remarkably similar to wheat in its early growth stages, making identification difficult until the distinctive jointed seed heads appear.

The plant’s seed heads break apart into segments at maturity, with each segment containing seeds that can remain dormant in soil for up to ten years.

When jointed goatgrass cross-pollinates with wheat, the resulting hybrid seeds contaminate grain harvests and can reduce crop quality and marketability.

The plant has developed resistance to several commonly used herbicides, making control increasingly challenging for farmers and gardeners alike.

Jointed goatgrass thrives in disturbed soils and can invade wheat fields, gardens, roadsides, and waste areas throughout Colorado.

Colorado restricts jointed goatgrass because of the economic threat it poses to the state’s wheat industry.

Property owners must prevent the plant from producing seed and implement management strategies to eliminate existing populations.

The plant emerges in fall or early spring, grows rapidly, and sets seed in late spring or early summer.

Removal is most effective when plants are young and haven’t yet developed extensive root systems or seed heads.

Hand-pulling works for small infestations if you remove plants before seeds mature and shatter.

Homeowners with vegetable gardens should be particularly vigilant because jointed goatgrass can easily invade cultivated areas and spread to nearby agricultural fields, creating problems for commercial growers.

14. Dyer’s Woad (Isatis Tinctoria)

Dyer’s woad has a fascinating history as the source of blue dye used by ancient civilizations, including possibly by Celtic warriors who painted their bodies before battle.

Despite its cultural significance, this European biennial has become a serious invasive threat in Colorado and throughout the western United States.

The plant produces masses of small yellow flowers in spring that create a striking display, which unfortunately attracted gardeners who introduced it to new areas.

After flowering, dyer’s woad develops distinctive purplish-black seed pods that dangle from branches, with each plant producing thousands of seeds.

Seeds remain viable in soil for up to ten years, creating a persistent seed bank that makes eradication extremely challenging.

Dyer’s woad develops a deep taproot that can extend several feet into the soil, allowing it to access water unavailable to most native plants.

This gives the plant a competitive advantage during drought conditions common in Colorado.

The plant releases chemicals into the soil that inhibit the germination and growth of other species, further enhancing its invasive success.

Colorado prohibits dyer’s woad statewide, requiring property owners to eradicate it when found.

The plant typically forms a flat rosette of blue-green leaves in its first year before sending up flowering stalks that can reach four feet tall in the second year.

Removal is most effective during the rosette stage when you can dig out the entire taproot before it becomes too established.

Monitor removal sites for several years because seeds in the soil will continue germinating and producing new plants.