15 Edible Wild Plants You Can Grow Right In California Home Gardens

California’s diverse climate makes it one of the best places in the country to grow edible wild plants—right at home.

These plants blur the line between garden and forage, offering flavor, nutrition, and resilience that traditional crops often lack.

Many thrive with minimal water, tolerate poor soil, and resist pests naturally.

They’re adapted to local conditions, making them easier to grow and more sustainable over time.

Once established, they often return year after year with little encouragement.

For California gardeners, growing edible wild plants is about reconnecting with food that belongs here.

These plants support pollinators, improve soil health, and deliver unique flavors you won’t find at the store.

As interest in sustainable gardening grows, these wild edibles are stepping into the spotlight—proving that sometimes the most valuable crops are the ones nature perfected long ago.

1. Miner’s Lettuce (Claytonia Perfoliata)

Gold rush miners discovered this leafy green growing wild across California hillsides, and it saved countless people from scurvy during tough times.

Today, miner’s lettuce remains one of the easiest native edible plants you can introduce to your home garden, especially if you love fresh salads.

This cool-season annual thrives in shady spots where other greens might struggle, making it perfect for those tricky garden corners.

Its round, saucer-shaped leaves grow on delicate stems and taste mild and slightly tangy, much like spinach but with a crunchier texture.

Small white flowers appear in spring, adding charm while signaling the plant is nearing the end of its season.

Miner’s lettuce self-sows freely, so once you plant it, expect volunteers to pop up year after year without much effort on your part.

It prefers moist, well-drained soil and partial shade, conditions common in many California yards during winter and early spring.

Harvest the leaves and stems when they’re young and tender for the best flavor and texture in salads or sandwiches.

Because it grows quickly and requires minimal care, even beginner gardeners find success with this historic green.

Adding miner’s lettuce to your garden connects you to California’s pioneering past while feeding your family nutritious, homegrown food.

2. California Poppy (Leaves And Seeds Only – Eschscholzia Californica)

California’s golden state flower isn’t just a symbol—it’s also a light source of foraged food when you know which parts to use.

While the vibrant orange petals steal the show, it’s the young leaves and seeds that have traditionally been consumed by indigenous communities.

The leaves carry a slightly bitter taste and are best harvested when tender and green, before the plant puts all its energy into blooming.

Seeds can be collected after flowers fade and seed pods dry, then used sparingly as a seasoning or nutrient boost in dishes.

California poppies self-sow with enthusiasm, spreading cheerful blooms across sunny garden beds and requiring almost no water once established.

They thrive in poor, sandy soil where other plants struggle, making them ideal for low-maintenance, drought-tolerant landscapes.

Most gardeners grow them for their stunning beauty rather than as a staple food source, but knowing their edible potential adds another layer of appreciation.

Always positively identify any wild plant before consuming it, and start with small amounts to ensure no adverse reactions.

These poppies attract pollinators like bees and butterflies, supporting your garden’s ecosystem while brightening your yard.

Growing California poppies honors the state’s natural heritage and offers a subtle connection to traditional foraging practices passed down through generations.

3. Wild Onion (Allium Unifolium)

If you’ve ever wanted to grow your own onions but found traditional varieties fussy, native wild onions might be your perfect match.

Allium unifolium produces slender green leaves and clusters of pretty pink flowers that rise above the foliage on tall stems in late spring.

Both the small bulbs and the tender greens carry a mild onion flavor, perfect for adding a fresh kick to salads, soups, or stir-fries.

This plant adapts well to California’s Mediterranean climate, needing little water once established and tolerating a range of soil types.

Correct identification is crucial, as some wild plants can resemble onions but lack the characteristic onion smell when leaves are crushed.

Always perform the smell test—if it doesn’t smell like onion, don’t eat it, no matter how similar it looks.

Wild onions grow from small bulbs that multiply over time, so your patch will expand naturally without needing to replant each year.

They prefer sunny to partly shaded locations and well-drained soil, conditions easy to provide in most California home gardens.

Harvest the greens by snipping them near the base, allowing the bulb to continue growing and producing more foliage.

Growing wild onions connects you to indigenous food traditions while adding beauty and flavor to your edible landscape with minimal effort required.

4. Yerba Buena (Clinopodium Douglasii)

Long before tea bags lined grocery store shelves, California’s indigenous peoples brewed soothing drinks from a humble groundcover called yerba buena.

The name means “good herb” in Spanish, a title earned through generations of use as a gentle, minty tea that soothes the stomach and refreshes the spirit.

This low-growing perennial spreads gracefully across shady garden spots, forming a fragrant carpet that releases its aroma when brushed or stepped on.

Yerba buena thrives in conditions where many edibles fail—under trees, along north-facing walls, or in dappled woodland garden settings.

Its small, rounded leaves carry a mild mint flavor, less intense than commercial mint but pleasant and calming when steeped in hot water.

The plant produces tiny white flowers in summer, adding delicate beauty while attracting beneficial insects to your garden ecosystem.

Because it spreads by runners, yerba buena fills in bare spots naturally, reducing weeds and creating a living mulch that conserves soil moisture.

Harvest sprigs throughout the growing season by snipping stems just above a leaf node, which encourages bushier growth and more leaves to pick later.

This native herb requires almost no maintenance once established, making it ideal for gardeners seeking low-effort edible landscaping options.

Brewing a cup of homegrown yerba buena tea connects you to California’s rich botanical heritage while offering a moment of calm in your busy day.

5. California Blackberry (Rubus Ursinus)

Nothing beats the taste of sun-warmed blackberries picked fresh from your own garden, and California’s native variety delivers flavor that commercial berries can’t match.

Rubus ursinus grows as a trailing vine rather than an upright shrub, making it perfect for training along fences, trellises, or garden borders.

The berries ripen in late summer, turning from green to red to deep purple-black, each one packed with sweet-tart flavor and nutritional benefits.

Native blackberries support local wildlife, providing food for birds and shelter for beneficial insects while producing fruit for your family.

These plants adapt to various California climates, from coastal areas to inland valleys, as long as they receive adequate water during the growing season.

The vines produce thorns, so wear gloves when harvesting or pruning, and consider planting them where you won’t accidentally brush against them.

California blackberries need some support to grow their best, so provide a trellis or let them scramble over a sturdy fence for easy picking.

Harvest berries when they’re fully colored and come off the vine with gentle pressure—underripe berries taste sour and won’t ripen further once picked.

These plants spread through underground runners, so contain them with barriers if you don’t want them taking over your entire garden space.

Growing native blackberries means enjoying delicious fruit while supporting California’s natural ecosystem, all from the convenience of your own backyard.

6. Wild Strawberry (Fragaria Vesca Or Fragaria Californica)

Imagine bending down in your garden to discover tiny, jewel-like strawberries hiding beneath delicate leaves—that’s the magic of growing native wild strawberries.

These petite fruits pack more flavor per bite than their supermarket cousins, offering an intensely sweet taste that makes up for their smaller size.

Wild strawberries grow as a spreading groundcover, sending out runners that root wherever they touch soil, gradually filling in bare spots with edible landscaping.

They thrive in partially shaded areas with consistent moisture, making them perfect for planting under fruit trees or along the edges of garden beds.

The white flowers appear in spring, followed by tiny berries that ripen throughout summer, providing treats for both gardeners and local birds.

Don’t expect pounds of fruit from wild strawberries—grow them for quality and flavor rather than quantity, savoring each perfect berry as a garden treasure.

These plants require minimal care once established, needing only occasional watering during dry spells and removal of old leaves in fall.

Native strawberries attract pollinators and beneficial insects while creating a lush, green carpet that suppresses weeds naturally.

Harvest berries when they’re fully red and fragrant, usually in the morning when they’re cool and at peak flavor.

Growing wild strawberries connects you to the land’s natural abundance while teaching children that the best things truly do come in small packages.

7. Chia (Salvia Columbariae)

Before chia became a trendy superfood, indigenous Californians harvested these tiny seeds from native plants growing wild across dry hillsides and valleys.

Salvia columbariae looks quite different from the tropical chia you might imagine—it’s a compact annual with purple flower spikes and deeply lobed leaves.

The plant thrives in California’s dry summer climate, requiring almost no supplemental water once established, making it perfect for water-wise gardens.

Chia grows easily from seed scattered directly in the garden in fall or early spring, germinating with the first good rain or watering.

The purple-blue flowers bloom on tall spikes in late spring, attracting hummingbirds and bees before developing into seed-laden heads.

When the seed heads turn brown and dry, usually by early summer, harvest them by cutting the stalks and shaking seeds into a container.

These tiny seeds can be eaten raw, ground into flour, or mixed with water to create the gel-like consistency that made chia pudding famous.

One plant produces hundreds of seeds, so a small patch can yield enough for personal use throughout the year with proper storage.

Chia plants self-sow readily, so allow some seed heads to scatter naturally if you want volunteers to return next season without replanting.

Growing native chia honors California’s agricultural heritage while producing one of nature’s most nutrient-dense foods right in your own garden space.

8. Prickly Pear Cactus (Opuntia Species)

Few plants embody California’s dry climate quite like the prickly pear cactus, with its paddle-shaped pads and jewel-toned fruit perched on top like crowns.

Both the young pads (called nopales) and the fruit (called tunas) are edible, offering unique flavors and textures to adventurous gardeners and cooks.

Prickly pears thrive in California’s hottest, driest regions, requiring almost no water once established and tolerating poor soil that would stress most edibles.

The pads taste slightly tangy and crisp when cooked, similar to green beans with a hint of lemon, and are popular in Mexican cuisine.

Fruit ripens in late summer, turning from green to red, purple, or yellow depending on the variety, with sweet flesh hiding beneath the spiny exterior.

Harvesting requires care—both pads and fruit are covered in tiny, hair-like spines called glochids that stick in skin and cause irritation.

Use thick gloves and tongs when picking, then carefully burn off or scrub away spines before preparing the cactus for eating.

Young, tender pads are best for cooking, while older pads become tough and fibrous, so harvest when they’re about hand-sized and still flexible.

Prickly pear cactus adds dramatic sculptural interest to xeriscape gardens while providing food and supporting desert-adapted wildlife.

Growing these remarkable plants means embracing California’s natural landscape while discovering flavors that connect you to southwestern culinary traditions spanning centuries.

9. Wild Fennel (Foeniculum Vulgare)

Drive along almost any California roadside in summer and you’ll spot tall, feathery plants with bright yellow flower clusters—that’s wild fennel, both blessing and curse.

This Mediterranean native has naturalized so successfully that it grows almost everywhere, offering free food to those who know how to harvest and use it.

Every part of fennel is edible—the feathery fronds, the seeds, the thick stems, and even the bulbous base if you dig it up young enough.

The flavor is distinctly licorice-like, strong and aromatic, which people either love or find overwhelming depending on their taste preferences.

Wild fennel grows enthusiastically, often reaching six feet tall or more, and self-sows with abandon if you don’t harvest the seed heads before they scatter.

Plant it in a contained area or large pot if you want to enjoy its culinary benefits without letting it take over your entire garden space.

Harvest the tender fronds throughout the growing season for flavoring fish, salads, and Mediterranean dishes with fresh, bright anise flavor.

Collect seeds when the flower heads turn brown and dry, then store them in airtight containers for use in cooking, tea, or as a digestive aid.

The thick stems can be peeled and cooked like celery, though they’re quite fibrous and work best in long-cooked dishes like soups or stocks.

Growing fennel intentionally means enjoying its bold flavor while managing its vigorous growth to prevent it from overwhelming more delicate garden neighbors.

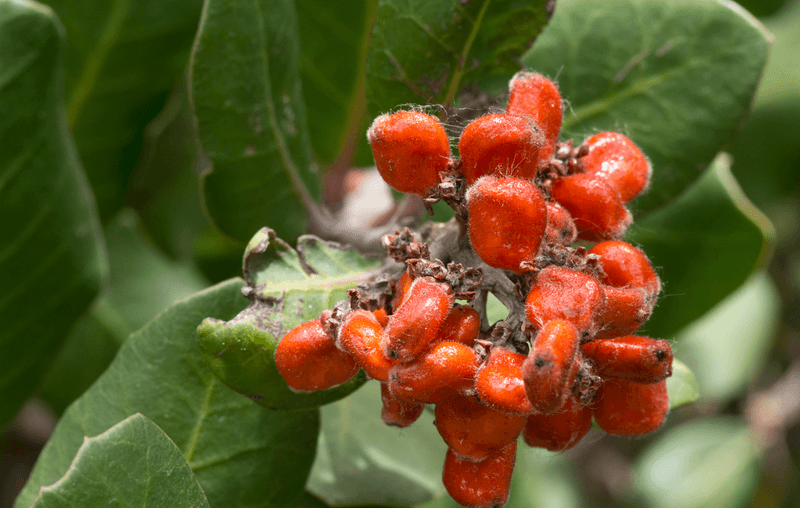

10. Manzanita (Berries – Arctostaphylos Species)

Manzanita shrubs define California’s chaparral landscape with their distinctive red bark, evergreen leaves, and clusters of small, apple-like berries that give the plant its Spanish name.

While most gardeners grow manzanita for its striking beauty and drought tolerance, indigenous peoples have long harvested the berries for food and beverages.

The berries are dry and mealy rather than juicy, with large seeds and minimal flesh, making them better suited for processing than eating fresh off the bush.

Traditionally, the berries were ground into flour or soaked in water to create a refreshing, slightly sweet drink similar to apple cider.

Manzanita thrives in California’s dry summer climate, requiring no supplemental water once established and tolerating poor, rocky soil that challenges most plants.

Choose varieties appropriate for your garden size, as manzanitas range from low groundcovers to large shrubs depending on the species.

The berries ripen in late summer and fall, turning from green to reddish-brown, and persist on the plant for months if not harvested.

Collect ripe berries by gently shaking branches over a sheet, then clean and process them within a few days for best results.

These native shrubs support local wildlife, providing cover for birds and food for various creatures while adding year-round structure to your landscape.

Growing manzanita means embracing California’s natural plant palette while connecting to food traditions that sustained people in this region for thousands of years.

11. Wild Grape (Vitis Californica)

California’s native wild grapes grow with such vigor that they’ll quickly cover any fence, arbor, or trellis you provide, creating shade while producing edible fruit.

The grapes are smaller than commercial varieties, with thicker skins and larger seeds, but they offer authentic grape flavor perfect for fresh eating or making preserves.

Vitis californica thrives along California’s waterways and can adapt to garden conditions with regular watering during the growing season and good drainage.

The vines produce beautiful foliage that turns brilliant colors in fall, adding ornamental value beyond just the fruit they provide.

Wild grapes ripen in late summer, turning from green to purple-black, though harvest timing varies depending on your specific location and microclimate.

Taste-test grapes before picking entire clusters, as ripeness affects flavor dramatically—underripe grapes are mouth-puckeringly sour while fully ripe ones are sweet and pleasant.

These vigorous vines need strong support structures and annual pruning to keep them manageable and productive in a home garden setting.

The fruit attracts birds, so consider netting your vines if you want to harvest grapes for yourself rather than feeding the neighborhood wildlife.

Wild grape leaves are also edible and can be used for wrapping foods, similar to cultivated grape leaves used in Mediterranean cooking.

Growing native grapes means enjoying homegrown fruit while supporting local ecology and creating beautiful, productive vertical elements in your edible landscape design.

12. Purslane (Portulaca Oleracea)

Most gardeners spend time pulling purslane from their vegetable beds, never realizing they’re removing one of the most nutritious plants on the planet.

This succulent groundcover contains more omega-3 fatty acids than almost any other leafy green, plus vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants in every crunchy, lemony bite.

Purslane grows as a sprawling mat of thick, reddish stems and paddle-shaped leaves that store water like tiny reservoirs, allowing the plant to thrive in heat and drought.

Small yellow flowers appear throughout summer, opening only in bright sunshine and closing on cloudy days or in late afternoon.

The entire above-ground plant is edible—stems, leaves, and flowers all offer a crisp texture and mild, slightly tangy flavor perfect for salads or cooking.

Once you recognize purslane’s value, you can intentionally grow it in garden beds, containers, or anywhere you want a productive, low-maintenance edible groundcover.

It self-sows enthusiastically, so one plant will provide volunteers for years to come, though you can easily control its spread by harvesting regularly.

Purslane prefers full sun and warm weather, growing vigorously throughout California’s long summer season when many other greens bolt or struggle.

Harvest by snipping stems near the base, which encourages branching and produces more tender growth for future harvests throughout the season.

Growing purslane intentionally transforms a common weed into a superfood, offering exceptional nutrition and flavor while requiring absolutely minimal care or resources.

13. Toyon (Heteromeles Arbutifolia)

Toyon’s bright red berries inspired early settlers to nickname Los Angeles Hollywood, as these shrubs covered the hills with their holiday-season color.

The berries are traditionally cooked before eating, as raw berries contain compounds that can cause stomach upset and are generally considered unpalatable in their fresh state.

Cooking transforms the berries into a sweet, edible fruit suitable for making jams, jellies, or sauces similar to cranberry preparations.

Toyon grows as a large, evergreen shrub that tolerates California’s dry summers once established, making it ideal for water-wise landscapes with edible potential.

The plant produces clusters of small white flowers in summer, followed by berries that ripen to brilliant red by late fall and winter.

Birds adore toyon berries, so these shrubs support wildlife while providing food for people willing to harvest and process the fruit properly.

Grow toyon in full sun to partial shade with good drainage, and give it space to reach its mature size of eight to fifteen feet tall and wide.

Harvest berries when they’re fully red and firm, then cook them thoroughly before eating—boiling, roasting, or processing into preserves all work well.

Never consume raw toyon berries, as traditional preparation methods exist for good reason and ensure the fruit is safe and palatable.

Growing toyon connects you to California’s natural landscape and indigenous food traditions while creating habitat for local wildlife and adding year-round beauty to your garden.

14. Lemonade Berry (Rhus Integrifolia)

California’s coastal communities have a special treat growing wild on bluffs and hillsides—lemonade berry, named for the refreshing drink made from its tart fruit.

The berries are small, sticky, and covered with a coating that tastes powerfully sour and citrusy when dissolved in water to create a traditional beverage.

Rhus integrifolia grows as a dense, rounded shrub with leathery evergreen leaves and excellent tolerance for coastal conditions, including salt spray and wind.

The plant thrives in California’s dry summer climate, requiring no supplemental water once established and tolerating poor soil that challenges less adapted species.

Small clusters of white or pinkish flowers appear in late winter to early spring, eventually developing into the reddish, sticky berries by summer.

To make lemonade berry drink, soak the berries in cold water for several hours, strain out the solids, and sweeten the resulting liquid to taste.

The shrub provides excellent habitat for birds and beneficial insects while creating a dense screen or hedge in coastal and inland California gardens.

Harvest berries when they’re fully developed and sticky to the touch, usually in mid to late summer depending on your location.

Lemonade berry is related to poison oak but lacks the irritating oils, making it safe to touch and harvest with bare hands.

Growing this coastal native means enjoying a unique, traditional beverage while creating a tough, beautiful landscape plant that connects you to California’s indigenous food heritage.

15. Nettle (Urtica Dioica)

Stinging nettle earned its name honestly—brush against the leaves with bare skin and you’ll experience an immediate, burning sensation that lasts for hours.

Yet this fierce plant transforms into one of the most nutritious wild greens available once you cook it, as heat neutralizes the stinging compounds completely.

Nettle grows vigorously in moist, rich soil, spreading through underground runners to form dense patches that can take over garden space if not contained properly.

The leaves are loaded with vitamins, minerals, and protein, making cooked nettle a powerhouse green comparable to spinach but with even more nutritional benefits.

Grow nettle in a contained area, raised bed, or large pot to enjoy its benefits without letting it escape into areas where you might accidentally touch it.

Harvest young leaves in spring when they’re tender and most nutritious, always wearing thick gloves and long sleeves to protect yourself from stings.

Once cooked, steamed, or dried, nettle becomes completely safe to eat and loses all stinging properties, tasting similar to spinach with a slightly earthy flavor.

The plant prefers partial shade and consistent moisture, conditions often found along garden edges, near downspouts, or in naturally damp areas of your yard.

Nettle supports beneficial insects and provides habitat for butterfly larvae, adding ecological value beyond its use as food for people.

Growing nettle intentionally means respecting its defensive nature while appreciating its remarkable nutritional profile and place in traditional herbalism and wild food culture.