Fruits That Actually Struggle In Arizona

Arizona’s scorching heat and arid climate create a challenging environment for many fruits that thrive elsewhere in the country. From my experience gardening in the Grand Canyon State, I’ve discovered that while some desert-adapted plants flourish, many common fruits simply can’t handle our extreme conditions.

The combination of intense summer temperatures, low humidity, alkaline soil, and limited water availability creates a perfect storm that leaves certain fruits struggling to survive, let alone produce a decent harvest. In Arizona’s harsh conditions, some fruits just don’t make the cut.

Below are fruits that have consistently shown difficulty adapting to Arizona’s unique growing environment. Whether you’re a hopeful gardener or simply curious about local agriculture, understanding these challenges might save you time, money, and disappointment.

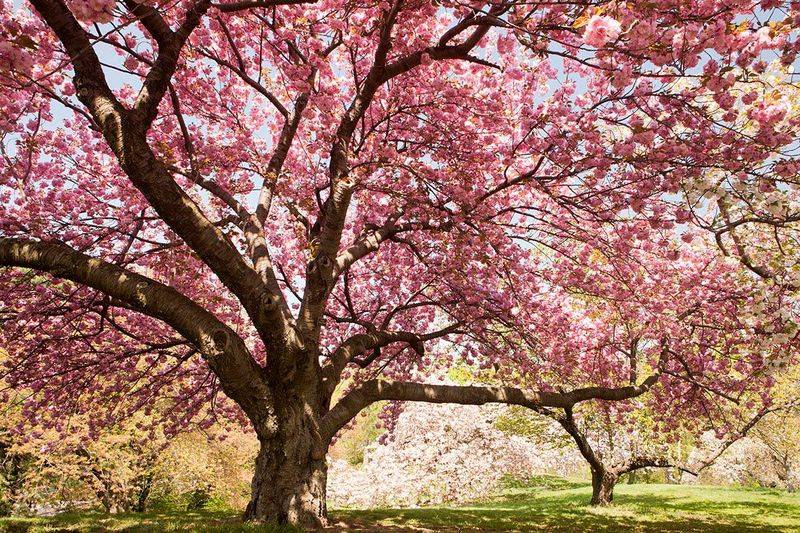

1. Cherries Need Winter Chill

Most cherry varieties require between 800-1,200 chill hours during winter to properly set fruit. In Arizona’s low desert regions, we rarely accumulate more than 400 hours below 45°F.

I tried growing Bing cherries in my Phoenix backyard for three seasons straight. The trees survived but never produced more than a handful of fruits. Without sufficient cold periods, cherry trees grow confused and typically yield poor harvests with bitter, undersized fruits.

2. Apples Face Sunburn Issues

Unlike their happy existence in cooler climates, apple trees suffer terribly from sunscald in Arizona. The intense direct sunlight burns the bark on the southwest side of trunks, creating open wounds that invite pests and disease.

During my attempts with Gala apples, the fruits that did develop often cooked on the tree before harvest. Only a handful of low-chill varieties like Anna or Dorsett Golden stand any chance here, and even those require special care with shade cloth and careful positioning.

3. Blueberries Battle Alkaline Soil

The naturally acidic-loving blueberry faces a major hurdle in Arizona’s highly alkaline soil. These berries require a soil pH between 4.5-5.5, while our native soil typically measures 7.5-8.5.

Years ago, I invested in extensive soil amendments and specialized containers for growing blueberries. Despite my efforts with acidifying fertilizers and peat moss, the plants remained stunted and produced tiny, flavor-lacking berries.

The constant battle against our water’s high pH makes blueberry cultivation an uphill struggle.

4. Kiwi Fruits Can’t Handle Dryness

Originating from humid regions of China, kiwi vines wilt rapidly in Arizona’s bone-dry atmosphere. The humidity levels here often drop below 10% during summer months, causing kiwi leaves to crisp along the edges.

My neighbor’s ambitious kiwi trellis project lasted exactly one summer before the plants surrendered to our climate. Even with regular watering, these moisture-loving vines struggle with transpiration rates that exceed their ability to uptake water through roots.

Fruit development typically halts midway, resulting in hard, inedible kiwis.

5. Raspberries Scorch In Summer

Summer temperatures regularly exceeding 110°F spell disaster for raspberry canes. These woodland-native berries simply cannot regulate their temperature effectively when exposed to our relentless sun.

The summer I attempted growing Heritage raspberries became a painful lesson in plant suffering. New growth would emerge in spring, only to be completely fried by June.

Any berries that managed to form were small, seedy, and lacking sweetness. Even with 50% shade cloth, raspberry plants typically decline after their first Arizona summer.

6. Peaches Struggle With Insufficient Chill

Many popular peach varieties require 700+ chill hours to properly break dormancy and produce fruit. Arizona’s brief, mild winters rarely provide enough cold exposure for proper bud development.

The few peaches that do manage to grow in my Tucson garden often split before ripening due to irregular development. When I’ve tried standard varieties like Elberta, the trees bloom erratically, with some branches flowering while others remain dormant.

Only specially bred low-chill varieties have any chance here, and even those produce inconsistently.

7. Cranberries Need Acidic Bogs

Cranberries naturally grow in acidic bogs with standing water, making them completely unsuited for Arizona’s dry landscape. These specialized berries require not just acidity but also a high water table and cool temperatures.

Commercial cranberry production involves flooding fields at specific times – a water-intensive practice impossible in our drought-prone state.

I’ve never personally attempted growing cranberries here, as their requirements are so dramatically opposed to our growing conditions that success would be impossible without creating an entirely artificial environment.

8. Blackberries Suffer Heat Stress

Blackberry canes often collapse under Arizona’s extreme heat stress, with fruit literally cooking on the vine before harvest. The berries’ delicate structure breaks down rapidly when temperatures exceed 100°F.

My experience with Triple Crown blackberries left me disappointed when the promising spring growth withered by early summer. The few berries that did develop were dry and lacking juiciness.

Thorny varieties seem especially vulnerable, with their dense growth creating heat traps that further stress the plants during our hottest months.

9. Plums Attract Devastating Pests

Arizona’s year-round warm climate creates the perfect breeding ground for plum-loving pests like plum curculio and Oriental fruit moths. Without a killing frost to break pest cycles, infestations build year after year.

The Santa Rosa plum tree in my backyard became a heartbreaking lesson in pest management. Beautiful spring blossoms gave way to developing fruits that were inevitably tunneled through by worms before ripening.

Our climate allows multiple pest generations per season, making organic growing particularly challenging without aggressive intervention.

10. Gooseberries Can’t Take The Heat

Native to cool northern regions, gooseberries simply melt down when faced with Arizona’s summer intensity. These shade-loving bushes evolved for forest understories, not desert exposures.

During my gooseberry experiment, the plants showed promising growth in early spring, then rapidly declined as temperatures climbed. By June, the leaves had scorched brown along the edges despite morning-only sun exposure.

The few berries that formed were sunburned on one side and remained hard and excessively tart, never developing their characteristic sweetness.

11. Pears Battle Bacterial Fireblight

Arizona’s combination of spring humidity and summer heat creates perfect conditions for fireblight, a bacterial disease that devastates pear trees. The infection spreads rapidly through blossoms and new growth, causing branches to blacken as if scorched by fire.

My Bartlett pear showed such promise its first year until spring rains triggered a fireblight outbreak. Within weeks, entire branches had died back, requiring aggressive pruning.

The stress from both disease and climate left the tree weakened and unproductive. Only Asian pear varieties show moderate resistance, but even they struggle with our conditions.

12. Currants Wither In Desert Sun

Currants evolved in northern forest environments, making them particularly ill-suited for Arizona’s intense sunlight. Their thin leaves quickly develop sunscald and crisp edges when exposed to our harsh rays.

I’ve tried growing both red and black currants in progressively shadier locations around my yard. Even with afternoon protection, the plants declined each summer.

The fruits that managed to form were small and quickly shriveled on the bush. Currants’ high water requirements further complicate their cultivation in our water-conscious region.

13. Sweet Cherries Miss Cold Winters

Sweet cherries are among the most chill-dependent fruits, requiring 1,000+ hours below 45°F. Arizona’s brief winters make proper dormancy impossible for most varieties.

When I attempted growing Rainier cherries, the trees leafed out erratically each spring, with some branches blooming while others remained dormant. The few cherries that formed were small and lacked sweetness.

Commercial cherry production in Arizona is virtually nonexistent for good reason – our climate simply doesn’t provide the winter conditions these fruits evolved to require.

14. Rhubarb Collapses In Summer

Though technically a vegetable used as fruit, rhubarb deserves mention as it spectacularly fails in Arizona summers. Its large leaves lose water faster than roots can replace it, leading to rapid collapse.

My rhubarb experiment lasted exactly one season. The plants established nicely during winter but completely melted down once May temperatures exceeded 95°F.

The stalks that did develop before the heat were thin and stringy rather than thick and juicy. Rhubarb is perhaps the perfect example of a northern plant utterly unsuited to desert conditions.

15. Elderberries Face Water Stress

Native elderberries grow along streams and in moist woodland edges – environments rarely found in Arizona. When cultivated here, they require excessive irrigation to prevent drought stress.

The American elderberry I planted required three times the water of my citrus trees yet still showed leaf curl during summer afternoons. While the plant survived, berry production was minimal and inconsistent.

The fruits that did form were smaller and more bitter than those grown in cooler, moister climates, making them hardly worth the water investment.

16. Grapes Suffer From Pierce’s Disease

European wine grapes struggle with Pierce’s disease, a bacterial infection spread by leafhoppers that thrive in Arizona’s climate. The disease blocks water-conducting tissues, causing vines to die back within 1-2 years.

My attempt with Cabernet Sauvignon vines ended in disappointment when they developed the telltale scorched leaf edges and irregular ripening. By the second summer, entire sections of the vines had died.

Only native American grape species and certain hybrids show meaningful resistance to this devastating disease that becomes particularly problematic in our warm winters.

17. Jostaberries Reject Desert Living

This gooseberry-black currant hybrid inherits both parents’ inability to handle Arizona conditions. Jostaberries develop leaf burn and stop fruit production when temperatures exceed 90°F.

The jostaberry plant I mail-ordered arrived looking promising but declined steadily through its first Arizona summer despite partial shade.

By August, most leaves had dropped and the few remaining showed severe edge burn. Like its parent plants, the jostaberry evolved for cool, humid conditions and simply cannot adapt to our hot, dry environment.

18. Quince Trees Battle Borers

Quince trees face a double threat in Arizona: heat stress weakens them while making them more attractive to devastating borers. These wood-boring insects target stressed trees, creating galleries that interrupt water flow.

The ornamental quince I planted showed initial promise but began declining in its second year. Inspection revealed the classic sawdust-like frass at the trunk base – evidence of borer infestation.

The combination of summer heat stress and pest pressure makes quince cultivation particularly challenging here, with trees rarely reaching their full productive potential.

19. Lingonberries Demand Acid And Cold

Closely related to cranberries, lingonberries require similar acidic, cool, and moist conditions completely contrary to Arizona’s environment. These northern berries simply cannot adapt to our alkaline soil and high temperatures.

I’ve never personally attempted growing lingonberries here, recognizing the futility after my blueberry struggles.

Commercial growers confirm that these Scandinavian natives require forest-like conditions with dappled shade, consistent moisture, and highly acidic soil – essentially the opposite of what Arizona naturally provides. Any success would require completely artificial growing conditions.