10 Garden Plants Facing Bans Or Restrictions In Arizona

Arizona gardens thrive under bright sun and wide skies, but not every plant gets a free pass.

Across the state, some familiar garden favorites are landing on watch lists or facing limits as officials work to protect land, water, and native species.

What once seemed like an easy planting choice can now raise red flags.

Plants that grow too fast, drink too much water, or spread beyond control can cause real problems in Arizona’s dry climate.

Some clog waterways, crowd out native plants, or increase fire risk.

Others escape backyard borders and push into open land, creating headaches that last far longer than a single season.

Many homeowners get caught off guard because these plants still look appealing and may even sit on store shelves.

Rules can also vary by county, making it tough to keep track of what’s allowed.

By the time restrictions kick in, removing an established plant can feel like an uphill battle.

Knowing which garden plants face bans or limits helps gardeners stay ahead of the curve.

Smart choices save time, money, and water while protecting Arizona’s unique landscapes.

Keeping gardens in step with the rules helps ensure outdoor spaces stay beautiful without adding to bigger environmental problems.

1. Fountain Grass (Pennisetum Setaceum)

Fountain grass arrived in Arizona gardens as an ornamental showpiece, admired for its graceful arching leaves and showy pink plumes that dance in the breeze.

Nurseries sold this African native extensively throughout the Southwest, and homeowners planted it freely in xeriscapes and decorative borders.

Nobody anticipated how aggressively it would spread beyond garden boundaries into wild desert areas.

This perennial grass produces thousands of seeds that wind carries across vast distances, establishing new colonies far from the original planting site.

Once established in natural areas, fountain grass outcompetes native vegetation for water and nutrients, particularly threatening Arizona’s saguaro forests and desert grasslands.

The dense growth creates continuous fuel loads that increase wildfire intensity and frequency, fundamentally changing fire patterns in ecosystems that evolved with infrequent burns.

Arizona prohibits the sale, distribution, and transportation of fountain grass throughout the state.

Property owners who currently have fountain grass should remove it completely, including the root system, to prevent further spread.

Several native alternatives offer similar ornamental appeal without environmental risks, including deer grass and various muhly grass species that provide flowing texture and seasonal color.

When selecting replacement plants for Arizona landscapes, choosing native species supports local ecosystems while reducing maintenance requirements and water consumption in the challenging desert climate.

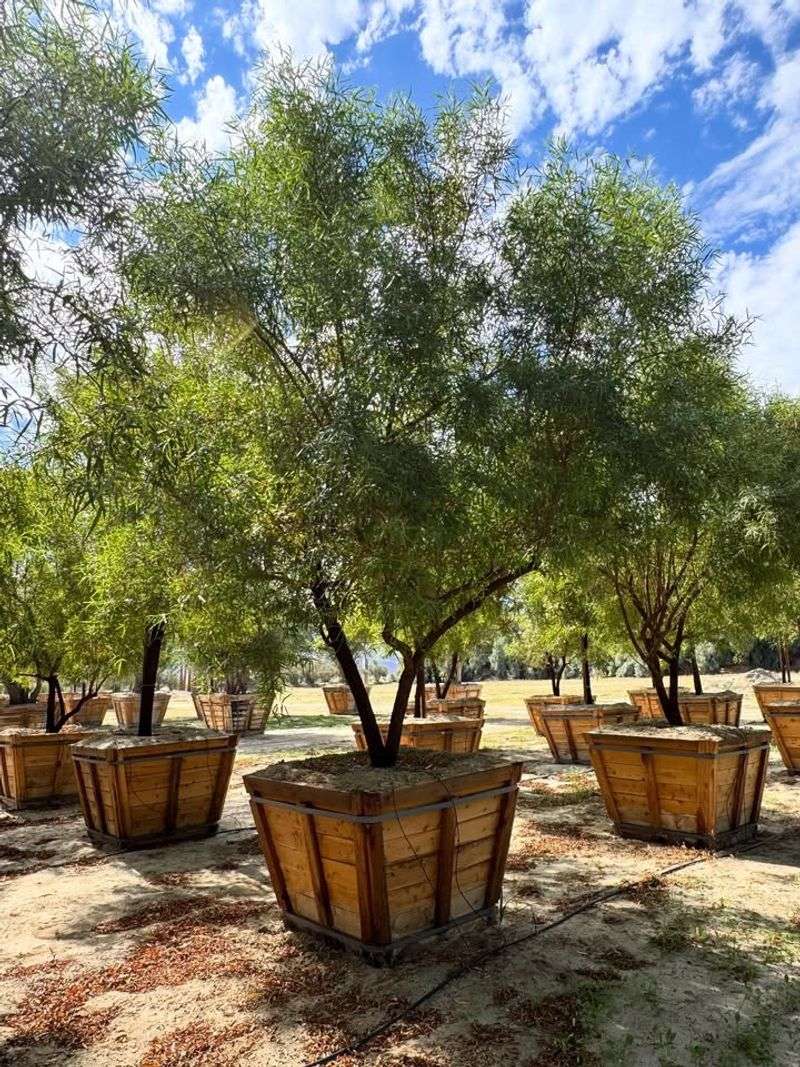

2. African Sumac (Rhus Lancea)

Landscapers throughout Arizona once considered African sumac the perfect shade tree for desert conditions.

This evergreen tree tolerates extreme heat, requires minimal water once established, and provides year-round greenery that many homeowners desired.

Developers planted thousands of these trees in subdivisions across the Phoenix metro area and other Arizona communities during housing booms.

The problem emerged gradually as African sumac began spreading into natural desert areas through bird-dispersed seeds.

The tree produces abundant berries that wildlife consume and deposit far from residential areas, establishing new populations along washes, roadsides, and desert preserves.

African sumac grows quickly and produces dense shade that prevents native plants from thriving underneath, fundamentally altering the structure of natural plant communities.

The species also consumes more water than native trees, potentially affecting groundwater levels in areas where it becomes established.

Several Arizona municipalities have restricted or banned new plantings of African sumac, though existing trees generally don’t require removal.

Phoenix and other cities no longer permit this species in new developments or public landscapes.

Homeowners planning landscapes in Arizona should consider native alternatives like desert willow, palo verde, or mesquite trees that provide shade without threatening natural ecosystems.

These native options support local wildlife, require less water, and maintain the authentic character of Arizona’s distinctive desert environment.

3. Buffelgrass (Pennisetum Ciliare)

Ranchers introduced buffelgrass to Arizona decades ago as livestock forage, hoping this African species would improve grazing lands in arid regions.

The grass thrived beyond anyone’s expectations, spreading rapidly across southern Arizona and establishing dense stands that now cover hundreds of thousands of acres.

What seemed like an agricultural solution became one of the most serious ecological threats facing the Sonoran Desert.

Buffelgrass creates a continuous carpet of highly flammable material that carries intense fires through areas where native plants never evolved to withstand flames.

Saguaro cacti, ironwood trees, and other iconic desert species suffer extensive damage from buffelgrass-fueled fires that burn hotter and spread faster than natural desert vegetation would allow.

The grass quickly resprouts after fire while native plants struggle to recover, creating a cycle that converts diverse desert ecosystems into buffelgrass monocultures.

Arizona law prohibits planting, selling, or transporting buffelgrass anywhere in the state.

Extensive removal efforts target infestations in Saguaro National Park, Tucson Mountain Park, and other protected areas throughout southern Arizona.

Property owners who discover buffelgrass should report it to local authorities and participate in removal efforts before it produces seeds.

Controlling this aggressive invader requires community-wide cooperation to protect the unique desert landscapes that define Arizona’s natural heritage and support countless native species found nowhere else on Earth.

4. Tamarisk (Tamarix Species)

Rivers and streams throughout Arizona once featured diverse riparian forests with cottonwoods, willows, and mesquite trees creating shaded corridors that supported abundant wildlife.

Tamarisk, also called saltcedar, has transformed many of these waterways into dense thickets dominated by a single non-native species.

Originally planted for erosion control and as ornamental shrubs, tamarisk escaped cultivation and spread aggressively along virtually every waterway in the Southwest.

Each mature tamarisk can consume up to 200 gallons of water daily, drawing moisture from streams and underground aquifers at rates far exceeding native vegetation.

The shrubs deposit salt from deep soil layers onto the surface, creating conditions where few other plants can survive.

Dense tamarisk stands provide poor habitat for native birds and wildlife compared to the diverse riparian forests they replaced.

Arizona’s limited water resources face additional pressure from the millions of tamarisk plants established along rivers, streams, and irrigation canals.

Arizona restricts the sale and planting of all tamarisk species, and extensive removal programs target infestations along major waterways.

The state has released specialized beetles that feed exclusively on tamarisk, providing biological control that complements mechanical removal efforts.

Property owners along waterways in Arizona should remove tamarisk and replace it with native willows, cottonwoods, or mesquite that support local ecosystems while using water more efficiently in this desert state.

5. Tree Of Heaven (Ailanthus Altissima)

Chinese immigrants brought tree of heaven to America in the 1700s, and this fast-growing species eventually spread across the continent.

Arizona’s urban areas and disturbed sites now host populations of this adaptable tree that thrives in poor soil, tolerates pollution, and grows rapidly in challenging conditions.

The species earned its heavenly name from its ability to reach toward the sky, but its impacts on Arizona ecosystems are far from divine.

Tree of heaven produces chemicals that inhibit the growth of surrounding plants, giving it a competitive advantage in areas where it becomes established.

A single mature tree generates thousands of wind-dispersed seeds that can travel considerable distances, establishing new populations in parks, vacant lots, and natural areas throughout Arizona.

The tree also spreads through root suckers that create dense clones, making removal particularly challenging once colonies form.

Broken roots left in the soil can generate new trees, complicating eradication efforts.

Some Arizona municipalities restrict tree of heaven, and state officials encourage property owners to remove existing specimens before they produce seeds.

The tree also serves as a host for spotted lanternfly, an invasive insect that threatens agriculture and could establish in Arizona if conditions allow.

When removing tree of heaven from Arizona properties, cutting alone proves insufficient, effective control requires treating stumps with appropriate herbicides to prevent resprouting.

Native alternatives like Arizona ash or desert willow provide similar rapid growth without the ecological problems associated with this aggressive invader.

6. Giant Reed (Arundo Donax)

Towering canes of giant reed line many Arizona waterways, creating bamboo-like groves that can reach 20 feet tall.

Landowners originally planted this Mediterranean species for erosion control, windbreaks, and even musical instrument production.

The plant’s vigorous growth seemed beneficial until it began spreading uncontrollably along rivers, streams, and irrigation canals throughout Arizona and the Southwest.

Giant reed forms impenetrable thickets that crowd out native willows, cottonwoods, and other riparian vegetation essential to Arizona’s limited wetland ecosystems.

The dense stands alter water flow patterns, increase flooding risks, and provide poor habitat for native wildlife compared to the diverse plant communities they replace.

Each plant consumes enormous quantities of water, significantly more than native vegetation, placing additional stress on Arizona’s overtaxed water resources.

The species spreads primarily through root fragments that water carries downstream, establishing new colonies wherever pieces lodge along riverbanks.

Arizona prohibits the sale, distribution, and transport of giant reed, and state agencies conduct extensive removal operations along major waterways.

Property owners should never plant giant reed and should remove existing stands completely, including underground rhizomes that can regenerate new growth.

Controlling this aggressive invader requires persistent effort, as tiny root fragments left behind can produce new plants.

Native alternatives for erosion control along Arizona waterways include seep willow, Goodding’s willow, and various native grasses that stabilize banks while supporting local ecosystems and using water more efficiently.

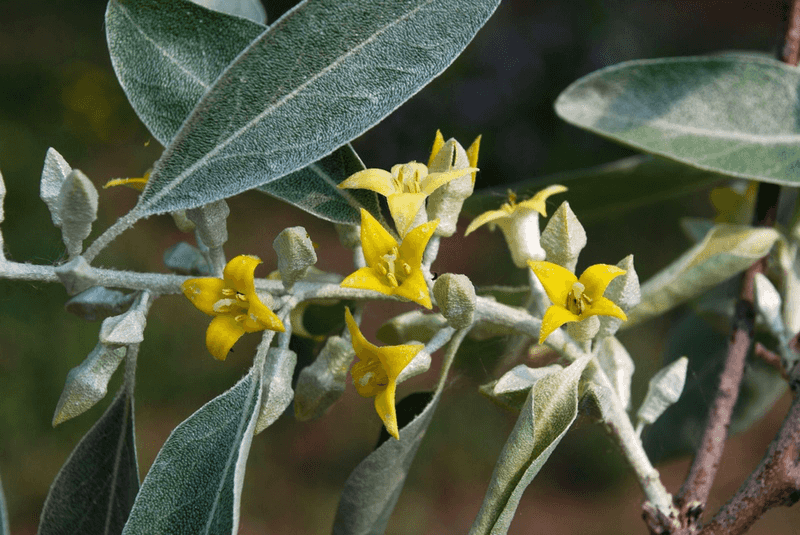

7. Russian Olive (Elaeagnus Angustifolia)

Silvery leaves and fragrant flowers made Russian olive a popular choice for Arizona windbreaks and ornamental plantings.

Farmers and ranchers appreciated the tree’s drought tolerance and ability to fix nitrogen in poor soils.

Wildlife seemed to benefit from the abundant olive-like fruits that birds eagerly consumed.

Everything about Russian olive appeared beneficial until its aggressive spread into natural areas revealed the problems this Eurasian native would cause.

Birds that feast on Russian olive fruits deposit seeds throughout Arizona’s riparian areas, where the tree establishes dense thickets along streams and rivers.

The species outcompetes native cottonwoods and willows for space, water, and nutrients, transforming diverse riparian forests into Russian olive monocultures.

Thorny branches create impenetrable barriers that reduce wildlife access to water and nesting sites.

The tree’s nitrogen-fixing ability actually harms native plants adapted to Arizona’s naturally nitrogen-poor soils, fundamentally altering soil chemistry in areas where it becomes established.

Arizona restricts Russian olive planting in many jurisdictions, and state officials recommend removing existing trees to prevent further spread.

The species has proven particularly problematic in northern Arizona riparian areas where removal projects aim to restore native vegetation.

Property owners seeking drought-tolerant trees for Arizona landscapes should consider native alternatives like desert willow, netleaf hackberry, or Arizona walnut that provide similar benefits without threatening natural ecosystems.

These native species support local wildlife, require minimal water once established, and maintain the ecological integrity of Arizona’s distinctive desert and riparian environments.

8. Saharan Mustard (Brassica Tournefortii)

Bright yellow flowers blanket Arizona deserts in years when Saharan mustard experiences population explosions.

This annual plant from North Africa and the Middle East arrived in the Southwest relatively recently but has spread with alarming speed across Arizona’s lower elevation deserts.

The cheerful displays might appear attractive, but these golden carpets represent a serious threat to native desert ecosystems that evolved over millennia.

Saharan mustard germinates earlier than native annual wildflowers, giving it a competitive advantage for water and nutrients in Arizona’s limited desert soils.

The plant grows rapidly, produces thousands of seeds per individual, and completes its life cycle before many native species even begin growing.

Dense stands prevent native wildflowers from establishing, reducing food sources for native pollinators and other insects that depend on indigenous plant species.

The species also increases fire risk by creating continuous fuel loads in areas where sparse native vegetation normally limits fire spread.

Arizona classifies Saharan mustard as a prohibited noxious weed, making it illegal to knowingly possess, transport, or sell this species anywhere in the state.

Land managers work to control infestations in protected areas throughout Arizona, particularly in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and other southern Arizona preserves.

Property owners who notice this yellow-flowered invader should remove plants before they set seed, preventing further spread.

Protecting Arizona’s spectacular native wildflower displays requires vigilance against aggressive non-native species that threaten the desert’s delicate ecological balance and natural beauty.

9. Camelthorn (Alhagi Maurorum)

Farmers and ranchers throughout Arizona have battled camelthorn infestations for decades, struggling to control this thorny invader that spreads aggressively through agricultural lands and natural areas.

This Middle Eastern native arrived in the Southwest through contaminated alfalfa seed and has since established populations in irrigated fields, along roadsides, and in disturbed sites across Arizona.

The plant’s name reflects its ability to survive on moisture that would barely sustain a camel.

Extensive root systems extending more than 20 feet deep allow camelthorn to access groundwater unavailable to most plants, giving it a significant advantage in Arizona’s arid climate.

The roots also spread horizontally, producing new shoots that create dense colonies covering large areas.

Sharp thorns make the plant difficult to remove manually and reduce the value of infested pastures for livestock grazing.

Camelthorn competes aggressively with crops in irrigated fields and displaces native vegetation in natural areas, particularly along washes and disturbed sites.

Arizona law prohibits the possession, transport, and sale of camelthorn, classifying it as a prohibited noxious weed throughout the state.

The species presents particular challenges for control because its deep root system makes complete removal extremely difficult.

Even small root fragments left in soil can regenerate new plants, requiring persistent monitoring and follow-up treatments.

Agricultural areas in Arizona continue fighting camelthorn infestations that reduce crop productivity and increase management costs.

Preventing the spread of this aggressive invader requires careful attention to seed sources and equipment cleaning to avoid inadvertently transporting plant material to uninfested areas.

10. Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum Salicaria)

Garden catalogs once promoted purple loosestrife as an attractive perennial for wet areas, highlighting the plant’s spectacular purple flower spikes that bloom throughout summer.

Gardeners across America planted this European native in water gardens and along ponds, appreciating the vertical color it provided.

Arizona’s limited wetlands seemed unlikely to support this moisture-loving species, but purple loosestrife has established populations in riparian areas and wetlands across the state wherever sufficient water exists.

A single mature plant produces millions of tiny seeds that water, wildlife, and wind disperse across vast distances.

Purple loosestrife forms dense stands that exclude native wetland plants, reducing habitat quality for waterfowl, amphibians, and other wildlife dependent on diverse wetland vegetation.

The species offers little food value for native insects and animals compared to the indigenous plants it replaces.

In Arizona’s limited wetland habitats, which constitute less than one percent of the state’s land area, purple loosestrife represents a particularly serious threat to ecosystems that support disproportionate biodiversity.

Arizona prohibits the sale, distribution, and planting of purple loosestrife throughout the state.

Property owners should never introduce this species and should remove any existing plants before they produce seeds.

Several native alternatives provide similar ornamental appeal for Arizona water features, including cardinal flower and various native rushes that support local ecosystems.

Protecting Arizona’s rare wetland habitats requires preventing aggressive non-native species from establishing in these critical areas that provide essential resources for countless native species in the predominantly arid landscape.