14 Garden Plants That Are Illegal Or Soon To Be Banned In South Carolina

South Carolina’s beautiful landscapes face a growing threat from aggressive invasive plants that spread rapidly, outcompete native species, and disrupt local ecosystems.

These problem plants may look harmless in home gardens, but many escape cultivation and take over forests, wetlands, and roadside areas, causing long-term ecological and economic damage.

In response, state officials and conservation experts have identified several ornamental and garden plants that pose the greatest risk, leading to new bans, restrictions, and strong recommendations against planting them.

Understanding which species are prohibited—or soon will be—helps gardeners make responsible choices, avoid unintentional harm, and support efforts to preserve the natural beauty and biodiversity of the Palmetto State.

Making informed decisions today ensures healthier landscapes, thriving wildlife, and a more sustainable environment for future generations.

1. Bradford Pear (Callery Pear)

Those pretty white flowers that cover Bradford Pear trees each spring might look charming, but this ornamental tree has become one of South Carolina’s most problematic invaders.

Originally planted along streets and in yards for its showy blooms, this species now spreads aggressively through forests and fields, crowding out native plants that wildlife depends on for food and shelter.

The tree produces thousands of small fruits that birds eat and spread everywhere through their droppings.

Within just a few years, a single Bradford Pear can create dense thickets that completely take over natural areas.

These trees also have weak branch structures that break easily during storms, creating hazards and maintenance headaches for property owners.

South Carolina has officially banned the sale and distribution of Bradford Pear trees to stop their spread.

Gardeners who already have these trees on their property should consider removing them and replacing them with native alternatives like Serviceberry or Flowering Dogwood.

These native species provide better support for local pollinators and birds while offering equally beautiful spring displays without the invasive problems.

2. Autumn Olive

Autumn Olive arrived in America with good intentions, planted for erosion control and wildlife food, but quickly revealed its aggressive personality.

This shrub grows incredibly fast, producing thousands of small red berries that animals find irresistible, leading to widespread seed dispersal across the countryside.

Each plant can produce up to 200,000 seeds annually, and those seeds remain viable in the soil for years, waiting for the right conditions to sprout.

The shrub’s silvery leaves make it easy to spot in natural areas where it forms dense stands that block sunlight from reaching native plants below.

Its ability to fix nitrogen in the soil actually changes the ground chemistry, making conditions less favorable for native species that evolved in South Carolina’s natural soil conditions.

Property owners often struggle to control Autumn Olive once it establishes itself because cutting the plants only encourages more vigorous regrowth from the roots.

The state has moved to restrict this plant to prevent further ecological damage.

Gardeners seeking shrubs for wildlife should choose native alternatives like Beautyberry or Elderberry, which provide food for birds without taking over entire landscapes.

3. Chinese Privet

Walking through South Carolina forests, you might encounter walls of Chinese Privet so thick that nothing else can grow beneath them.

This evergreen shrub creates a living barrier that blocks all light from reaching the forest floor, preventing native wildflowers and tree seedlings from surviving.

Chinese Privet spreads through both seeds and root sprouts, making it extremely difficult to control once established.

Birds eat the small purple-black fruits and deposit seeds throughout natural areas, creating new infestations far from the original plants.

The shrub tolerates shade, sun, wet soil, and dry conditions, giving it an unfair advantage over native species that evolved in specific habitats.

Forest managers spend countless hours and resources trying to remove this invasive shrub from public lands.

Its dense growth also reduces habitat quality for ground-nesting birds and other wildlife that need open understory spaces.

South Carolina has recognized the serious threat this plant poses and included it on the state’s prohibited list.

Homeowners looking for evergreen screening should consider native options like American Holly or Wax Myrtle, which provide year-round greenery without harming natural ecosystems.

4. Japanese Privet

Garden centers once promoted Japanese Privet as the perfect hedge plant, and homeowners loved its fast growth and dense foliage.

However, this seemingly well-behaved garden plant has a secret life as an aggressive invader that escapes cultivation and spreads into wild areas.

Similar to its Chinese cousin, Japanese Privet produces abundant fruits that birds distribute widely, creating new populations in forests, wetlands, and along stream banks.

The plant forms dense thickets that exclude native vegetation and reduce biodiversity in affected areas.

Its rapid growth rate allows it to quickly dominate disturbed sites, preventing natural succession and forest recovery.

The shrub’s tolerance for various growing conditions makes it particularly troublesome in South Carolina’s diverse habitats.

It grows equally well in sun or shade, wet or dry soil, and resists most common plant diseases.

State regulations now restrict this species to prevent further environmental damage.

Gardeners seeking privacy hedges have excellent native alternatives available, including Yaupon Holly and Carolina Cherry Laurel, both of which provide screening without the invasive tendencies.

These native choices also support local insects and birds that depend on native plants for survival.

5. Multiflora Rose

Farmers once planted Multiflora Rose as living fences to contain livestock, but this thorny shrub soon proved to be a terrible mistake.

Its arching canes root wherever they touch the ground, creating impenetrable tangles that consume pastures, roadsides, and forest edges.

Each plant produces clusters of small white flowers followed by tiny rose hips that birds eagerly consume and spread far and wide.

A single mature plant can generate hundreds of thousands of seeds annually, and those seeds remain viable in the soil for up to twenty years.

The dense, thorny thickets make infested areas completely unusable for recreation or agriculture while providing poor habitat for wildlife compared to native plant communities.

Controlling this rose requires persistent effort because cutting stems triggers vigorous regrowth from the root crown.

The sharp thorns make manual removal difficult and painful work.

South Carolina has moved to restrict this plant due to its significant negative impacts on agriculture and natural areas.

Gardeners wanting roses in their landscapes should stick with cultivated varieties that don’t spread aggressively, or better yet, choose native roses like Carolina Rose or Swamp Rose that support local ecosystems beautifully.

6. Japanese Knotweed

Japanese Knotweed might look like an attractive bamboo-like plant, but beneath the surface lurks one of the world’s most destructive invasive species.

Its underground stems, called rhizomes, spread aggressively and can push through concrete, asphalt, and building foundations, causing serious structural damage to homes and infrastructure.

A tiny fragment of rhizome smaller than your fingernail can grow into a whole new plant, making this species nearly impossible to eliminate once established.

The plant grows incredibly fast during summer, shooting up to ten feet tall and forming dense stands that completely exclude all other vegetation.

These monocultures provide little value for native wildlife and destabilize stream banks, leading to erosion problems.

Property values can actually decrease when Japanese Knotweed infests a site because mortgage lenders recognize the expense and difficulty of controlling this plant.

South Carolina has banned this species to protect both natural areas and private property.

Anyone who discovers Japanese Knotweed should contact their local extension office immediately for guidance on proper removal techniques.

Never try to control it by digging or tilling, as this only spreads fragments and makes the problem exponentially worse throughout your property.

7. Nandina

Garden centers still sell Nandina, also called Heavenly Bamboo, but this popular ornamental shrub has a dark side that many gardeners don’t know about.

While it looks attractive with its colorful foliage and bright red berries, those berries contain compounds that harm songbirds when consumed in large quantities.

Cedar waxwings and other fruit-eating birds sometimes gorge on Nandina berries during winter when other food sources become scarce.

The berries provide little nutritional value while potentially causing serious health problems for the birds that eat them.

Additionally, Nandina has begun escaping cultivation in South Carolina, spreading into natural areas where it competes with native shrubs that provide better food sources for wildlife.

The plant’s ability to tolerate various growing conditions and its persistent berry production make it an effective spreader.

Birds deposit seeds in forests and along stream banks, creating new populations away from cultivated areas.

South Carolina is moving toward restrictions on this species due to both its invasive potential and its negative impacts on native birds.

Gardeners seeking colorful foliage and winter interest should consider native alternatives like Beautyberry, Winterberry Holly, or Sumac species that provide genuine benefits to local wildlife while creating equally stunning landscape displays.

8. Tree Of Heaven

Despite its heavenly name, this tree creates hellish problems for South Carolina landowners and natural areas.

Tree of Heaven grows with astonishing speed, reaching heights of 60 feet or more while producing chemicals that prevent other plants from growing nearby through a process called allelopathy.

Each female tree generates tens of thousands of winged seeds that wind carries far from the parent plant, establishing new infestations across the landscape.

The tree also spreads through root suckers, sending up new stems that can appear dozens of feet from the main trunk.

When you cut down a Tree of Heaven, the root system responds by producing numerous new shoots, often creating a worse problem than before.

This species has become particularly concerning because it serves as the preferred host for spotted lanternfly, an invasive insect that damages crops and ornamental plants.

The combination of these two invasive species creates compounding problems for agriculture and forestry.

South Carolina has banned Tree of Heaven to slow its spread and reduce suitable habitat for spotted lanternfly.

Property owners should remove these trees using proper techniques that prevent regrowth, and replace them with native shade trees like Oak, Hickory, or Tulip Poplar that support hundreds of native insect species.

9. Chinese Tallow Tree

Coastal South Carolina faces a serious threat from Chinese Tallow Tree, sometimes called Popcorn Tree because of its white, waxy seeds.

This attractive tree displays brilliant fall colors that rival any native species, but its beauty masks an aggressive invasive nature that transforms diverse coastal forests into single-species stands.

The tree produces enormous quantities of seeds that remain viable for years, creating persistent seed banks in the soil.

Birds and water both spread the seeds, allowing rapid colonization of new areas.

Chinese Tallow tolerates flooding, drought, salt spray, and poor soil, making it especially problematic in coastal regions where it invades marshes, maritime forests, and disturbed sites.

Once established, these trees grow quickly and cast dense shade that prevents native plants from surviving beneath their canopies.

The resulting monocultures provide poor habitat for native wildlife compared to diverse natural plant communities.

All parts of the tree contain compounds that can irritate skin and cause digestive problems if consumed.

South Carolina has prohibited this species to protect valuable coastal ecosystems.

Homeowners wanting fall color should choose native trees like Sweetgum, Black Gum, or Red Maple that provide spectacular autumn displays while supporting local biodiversity and ecosystem health.

10. Cogongrass

Cogongrass ranks among the world’s worst invasive plants, and South Carolina takes its threat very seriously.

This aggressive grass spreads through both seeds and underground rhizomes, forming dense mats that completely exclude all other vegetation and dramatically increase fire risk in affected areas.

The plant’s sharp leaf edges can actually cut skin, making infested areas difficult and painful to walk through.

Cogongrass contains very little nutritional value for wildlife or livestock, essentially creating biological deserts wherever it dominates.

Its extensive root system makes the grass extremely difficult to control, and disturbance through mowing or tilling only spreads rhizome fragments that grow into new plants.

Forest managers consider Cogongrass one of their most serious challenges because it prevents tree regeneration and alters natural fire regimes.

The grass produces highly flammable material that burns extremely hot, potentially harming even fire-adapted native species.

Equipment moving between infested sites can transport rhizome fragments, spreading the grass to new locations.

South Carolina strictly prohibits Cogongrass and requires reporting of any infestations.

Anyone who spots this grass should contact their county extension office immediately.

Never attempt to control it yourself without expert guidance, as improper techniques often make infestations worse rather than better.

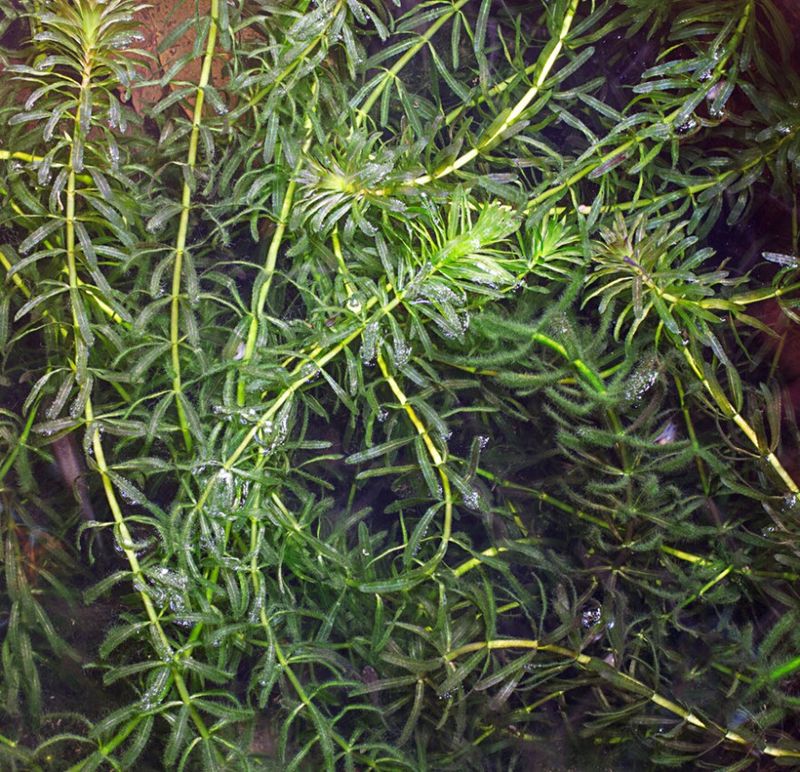

11. Hydrilla

Beneath the surface of South Carolina’s lakes and ponds, Hydrilla creates underwater jungles that choke out native aquatic plants and make swimming, boating, and fishing nearly impossible.

This submerged plant grows with incredible speed, sometimes adding a foot of length per day during peak growing season.

Hydrilla reproduces through multiple methods including fragments, tubers, turions, and sometimes seeds, making it extremely difficult to control once established.

A tiny plant fragment broken off by a boat propeller can drift downstream and start a whole new infestation.

The plant forms dense mats that reach the water surface, blocking sunlight from native aquatic plants and creating stagnant conditions that reduce oxygen levels for fish.

Recreation areas infested with Hydrilla become unusable, and property values along affected waterways can decline significantly.

Control efforts cost millions of dollars annually across the southeastern United States.

South Carolina strictly prohibits possession, sale, and transport of Hydrilla.

Boaters should always clean their vessels, trailers, and equipment before moving between water bodies to prevent accidentally spreading this destructive plant.

If you discover Hydrilla in a previously uninfested water body, report it immediately to state natural resource officials so control efforts can begin before the infestation expands further.

12. Water Hyacinth

Water Hyacinth produces gorgeous purple flowers that make it a popular aquarium and water garden plant, but this floating beauty becomes a monster when released into natural waterways.

The plant reproduces at an astonishing rate, doubling its population in as little as two weeks under ideal conditions.

Dense mats of Water Hyacinth can completely cover ponds, lakes, and slow-moving streams, blocking all light from reaching underwater plants and reducing oxygen levels that fish need to survive.

The thick vegetation impedes boat traffic, clogs water intake pipes, and provides breeding habitat for mosquitoes.

In tropical climates, Water Hyacinth has rendered entire waterways completely unusable for transportation, recreation, or water supply.

While South Carolina’s winters usually prevent permanent establishment, climate change may allow this species to survive year-round in the state’s warmer regions.

Even temporary summer infestations cause significant ecological and economic damage.

The state prohibits Water Hyacinth to prevent these problems.

Water gardeners should never release aquatic plants into natural water bodies, even if you think they won’t survive winter.

Choose native floating plants like American Lotus or native water lilies for water features, and always dispose of unwanted aquatic plants in the trash rather than in lakes or streams.

13. Water Lettuce

Water Lettuce looks like small floating heads of lettuce drifting on the water surface, and its neat appearance makes it popular for ornamental ponds.

However, this innocent-looking plant shares the same aggressive tendencies as its cousin Water Hyacinth, rapidly multiplying to cover entire water bodies.

Each plant produces offsets on short stems that break away to form new independent plants, allowing populations to expand exponentially.

Under favorable conditions, Water Lettuce can double its coverage every few days.

The floating mats block sunlight, reduce oxygen, increase water temperature, and create stagnant conditions that harm fish and other aquatic life.

Dense Water Lettuce infestations interfere with recreational activities and provide habitat for disease-carrying mosquitoes.

The plant’s ability to absorb heavy metals from water might sound beneficial, but this actually concentrates toxins in plant tissues that then enter the food chain when animals consume the vegetation.

South Carolina prohibits Water Lettuce to protect the state’s valuable aquatic ecosystems.

Pond owners seeking floating plants should use native species like Golden Club or Floating Hearts that provide similar aesthetic appeal without the invasive risks.

Remember that dumping aquarium or pond plants into natural water bodies is both illegal and ecologically harmful to South Carolina’s aquatic environments.

14. Giant Salvinia

Giant Salvinia might be the smallest plant on this list, but it creates some of the biggest problems for South Carolina’s water bodies.

This floating fern forms thick mats that can grow so dense they actually support the weight of small animals walking across the water surface.

The plant reproduces vegetatively, with each piece capable of growing into a new colony.

Under optimal conditions, Giant Salvinia can double its coverage every few days, quickly transforming open water into solid green carpets.

These mats block all light penetration, causing underwater plants to perish and dissolved oxygen levels to plummet, creating conditions where fish suffocate.

Giant Salvinia infestations make water bodies completely unusable for swimming, boating, and fishing while dramatically reducing property values along affected shorelines.

The plant’s tiny size makes it easy to accidentally transport on boats, trailers, and fishing equipment, leading to rapid spread between water bodies.

South Carolina has banned Giant Salvinia due to its devastating impacts on aquatic ecosystems and recreation.

Preventing its spread requires vigilance from everyone who uses the state’s lakes and rivers.

Always clean and dry your boat and equipment thoroughly before moving between different water bodies, and never release aquatic plants from aquariums or ponds into natural waterways.