How Oregon Gardeners Keep Leafy Greens Growing Through Winter

Oregon’s mild winters make year-round gardening possible with the right approach.

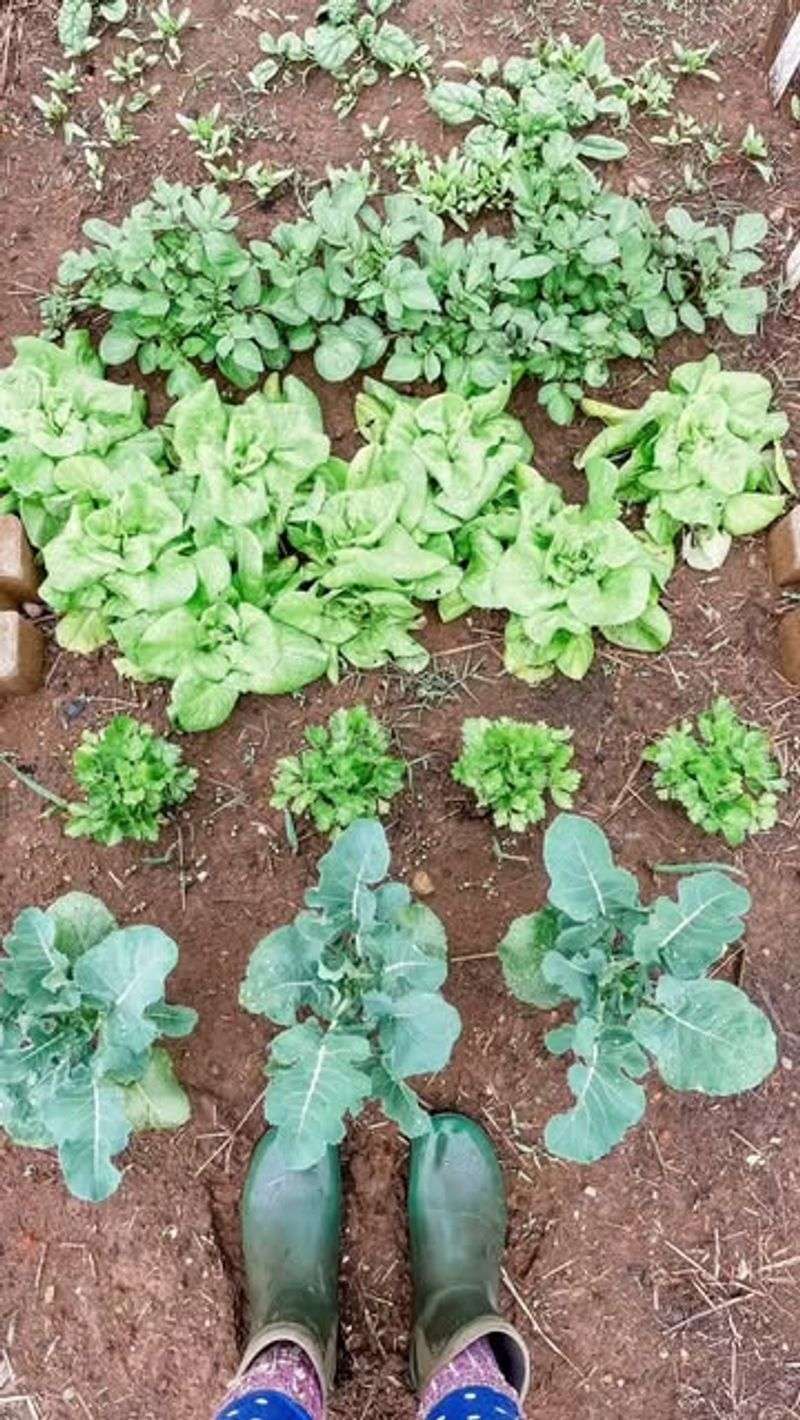

Gardeners keep leafy greens growing through winter by choosing cold-hardy varieties and protecting them from excess rain rather than extreme cold.

Unlike harsher climates, Oregon’s biggest winter challenge is moisture, not freezing temperatures.

Greens like kale, spinach, and mache grow slowly but steadily when planted early and protected with row covers or cold frames. Raised beds and good drainage are key.

By working with Oregon’s climate instead of fighting it, gardeners enjoy fresh greens even during the shortest days of the year.

Choosing Cold-Hardy Greens Instead Of Summer Varieties

Some vegetables simply handle cold weather better than others, and that makes all the difference when winter arrives in Oregon.

Kale stands as one of the toughest options, with leaves that actually taste sweeter after a few frosts touch them.

Spinach grows steadily through winter, producing tender leaves even when temperatures hover near freezing.

Mache, also called corn salad, thrives in cool soil and keeps growing when most other plants have stopped.

Arugula adds a peppery kick to salads and tolerates cold weather far better than delicate summer lettuces.

Asian greens like bok choy, mizuna, and tatsoi bring variety to winter meals while resisting frost damage.

Summer lettuce varieties often turn bitter or bolt when temperatures drop, making them poor choices for Oregon winters.

Cold-hardy greens have thicker cell walls and produce natural sugars that act like antifreeze in their leaves.

This biological adaptation allows them to survive freezing nights and continue photosynthesis during short winter days.

Choosing the right varieties from the start saves gardeners frustration and ensures a steady harvest.

Seed packets usually indicate cold tolerance, so reading labels carefully helps gardeners select winners.

Investing in proven cold-hardy varieties means less wasted effort and more fresh greens on the dinner table all winter long.

Planting Early Enough For Roots To Establish Before Cold Sets In

Timing matters more than most gardeners realize when it comes to winter greens success.

Plants need strong root systems before cold weather arrives, and that takes several weeks of growing time.

Sowing seeds or transplanting seedlings in late summer or early fall gives greens a head start.

By the time November arrives, well-established plants can handle dropping temperatures without stress.

Roots anchor plants firmly in the soil and absorb nutrients even when leaf growth slows down dramatically.

Waiting too long to plant means greens never develop the foundation they need to survive winter conditions.

Seedlings planted in October often just sit in cold soil without growing much until spring returns.

Early planting allows greens to reach a decent size before daylight hours shrink and temperatures fall.

Larger plants with deeper roots tolerate frost better than tiny seedlings struggling to get started.

Gardeners in Oregon typically aim to plant winter greens between mid-August and mid-September for best results.

This window gives plants six to eight weeks of relatively warm weather to grow strong.

Checking local frost dates and counting backward helps gardeners plan the perfect planting schedule.

A calendar marked with planting deadlines keeps gardeners on track and prevents last-minute panic.

Preparation in late summer pays off with steady harvests throughout the coldest months ahead.

Using Row Covers To Trap Ground Heat

Lightweight fabric row covers create a protective barrier that makes a surprising difference in plant survival.

These covers trap heat radiating from the soil during the day and release it slowly throughout the night.

Even a few degrees of extra warmth can prevent frost damage and keep leaves tender instead of frozen.

Row covers also shield plants from harsh winds that can dry out leaves and stress plants unnecessarily.

Many Oregon gardeners drape covers directly over greens or support them with hoops to create a tunnel.

The fabric allows sunlight, air, and water to pass through while blocking the worst weather conditions.

Heavyweight row covers provide more insulation but may block too much light during Oregon’s already dim winters.

Lightweight versions offer a better balance, protecting plants without cutting off essential sunlight for photosynthesis.

Securing covers with rocks, stakes, or soil along the edges prevents wind from blowing them away.

Removing covers on warmer days allows plants to breathe and prevents moisture buildup that encourages disease.

Row covers cost less than building permanent structures and store easily when not in use.

Reusing covers year after year makes them an economical choice for budget-conscious gardeners.

This simple tool extends the growing season by several weeks and protects tender leaves from unexpected cold snaps.

Growing Greens In Raised Beds For Better Drainage

Oregon winters dump incredible amounts of rain, and that moisture can drown plant roots faster than cold temperatures ever could.

Raised beds lift soil above ground level, allowing excess water to drain away instead of pooling around roots.

Waterlogged soil suffocates roots by cutting off oxygen, which plants need just as much as water.

Greens growing in soggy soil often develop yellowing leaves, stunted growth, and rotting roots that smell terrible.

Building raised beds just eight to twelve inches high makes a dramatic difference in drainage.

Filling beds with a mix of compost, topsoil, and perlite creates fluffy soil that drains quickly after heavy rains.

Well-draining soil also warms up faster on sunny winter days, giving plant roots a boost of activity.

Raised beds keep greens cleaner because rain splash does not coat leaves with mud and debris.

The improved air circulation around raised beds helps leaves dry faster, reducing fungal disease problems.

Gardeners with limited space can fit several raised beds in small yards and still grow plenty of winter greens.

Wooden, metal, or stone borders hold soil in place and make beds look neat and organized.

Investing in raised beds pays off year after year with healthier plants and bigger harvests.

This strategy proves especially valuable in Oregon, where winter rain challenges even experienced gardeners regularly.

Taking Advantage Of Oregon’s Mild Winter Temperatures

Western Oregon enjoys a climate advantage that many other regions simply cannot match during winter months.

Temperatures often stay above freezing for weeks at a time, allowing greens to grow slowly but steadily.

Coastal areas rarely see hard freezes, making them ideal for year-round vegetable gardening with minimal protection.

Even inland valleys like the Willamette experience milder winters compared to most of the United States.

Greens need temperatures above 40 degrees Fahrenheit to photosynthesize and produce new leaves.

Oregon’s winter climate hovers right in that sweet spot where growth continues without needing heated greenhouses.

Gardeners in colder states must invest in expensive heating systems or accept that winter gardening is impossible.

Oregon gardeners can skip those costs and still enjoy fresh salads by working with the natural climate.

Understanding local microclimates helps gardeners identify the warmest spots in their yards for planting greens.

South-facing areas near walls or fences capture extra sunlight and stay warmer than open garden spaces.

Taking advantage of these natural warm pockets maximizes growth without any additional equipment or effort.

Oregon’s maritime climate brings consistent moisture and moderate temperatures that greens genuinely love.

This natural advantage makes winter gardening easier and more productive than in most other parts of North America.

Mulching Soil To Regulate Temperature

Temperature swings stress plants more than steady cold, and mulch acts like a blanket that smooths out those fluctuations.

Spreading a layer of straw, dried leaves, or shredded bark around greens insulates soil from rapid temperature changes.

Mulch keeps soil warmer on cold nights and cooler on unusually warm winter days when sunshine breaks through clouds.

This stability allows roots to function normally instead of going into shock from sudden temperature shifts.

A two to three inch layer of mulch works well without smothering plants or blocking water from reaching roots.

Organic mulches break down slowly over winter, adding nutrients to soil while protecting plant roots simultaneously.

Straw makes an excellent mulch choice because it stays loose and allows air and water to penetrate easily.

Dried leaves work well too, though they may compact over time and need fluffing occasionally.

Mulch also prevents soil erosion during heavy Oregon rainstorms that can wash away valuable topsoil.

Weeds struggle to germinate through mulch layers, reducing competition for nutrients and water around greens.

Applying mulch in late fall before the coldest weather arrives gives plants maximum protection when they need it most.

Pulling mulch back slightly in early spring allows soil to warm up faster as daylight hours increase.

This simple technique costs almost nothing but delivers significant benefits for winter greens throughout the season.

Harvesting Outer Leaves Instead Of Pulling Whole Plants

Many gardeners make the mistake of harvesting entire plants at once, which ends their winter greens supply immediately.

Picking only the outer leaves allows the center of the plant to keep growing and producing more foliage.

Kale, chard, and many Asian greens respond beautifully to this cut-and-come-again harvesting method.

New leaves emerge from the center while gardeners enjoy fresh greens from the same plants week after week.

This approach maximizes harvest from limited garden space and keeps plants productive throughout winter months.

Removing outer leaves also improves air circulation around plants, reducing moisture buildup that encourages fungal problems.

Using clean, sharp scissors or garden shears makes neat cuts that heal quickly without damaging plants.

Tearing leaves by hand can injure stems and create entry points for diseases during wet Oregon winters.

Harvesting regularly encourages plants to produce more leaves instead of putting energy into flowering and seed production.

Most greens taste best when leaves are young and tender rather than old and tough.

Picking frequently ensures a constant supply of the most flavorful leaves for salads and cooking.

Plants harvested this way can produce for four to six months if protected from severe weather.

This technique transforms a single planting into a long-term food source that keeps giving all winter long.

Using Cold Frames Or Low Hoops

Cold frames and low hoops function like mini greenhouses without requiring electricity or complicated construction.

These simple structures trap solar heat during the day and protect plants from wind and frost at night.

A cold frame typically consists of a wooden or metal box with a transparent lid that tilts open for ventilation.

Low hoops use flexible PVC or metal pipes bent over beds and covered with plastic or row cover fabric.

Both designs create a warmer microclimate that extends the growing season by several weeks on both ends of winter.

Temperatures inside cold frames can be 10 to 20 degrees warmer than outside air on sunny days.

Ventilation becomes important on mild days to prevent overheating, which can damage plants just as badly as cold.

Propping lids open or rolling up sides of hoop houses allows excess heat to escape and fresh air to circulate.

Cold frames work especially well for shorter greens like spinach and lettuce that fit comfortably under low covers.

Taller structures accommodate larger plants like mature kale and chard without crowding or bending leaves.

Many Oregon gardeners build simple cold frames from recycled windows and scrap lumber for minimal cost.

These structures last for years with basic maintenance and provide reliable protection season after season.

Investing a weekend in building cold frames or hoops pays off with abundant winter harvests and healthier plants.

Protecting Greens From Heavy Rain Rather Than Snow

Most gardening advice focuses on protecting plants from snow and ice, but Oregon gardeners face a different challenge entirely.

Heavy rain pounds down week after week, battering tender leaves and creating persistently wet conditions that encourage disease.

Excessive moisture on leaves promotes fungal infections like mildew and leaf spot that can ruin entire crops.

Covering greens with transparent plastic or greenhouse panels keeps rain off leaves while still allowing light to reach plants.

Creating angled covers ensures water runs off instead of pooling on top and eventually collapsing the structure.

Good air circulation under covers prevents humidity from building up to levels where fungal spores thrive.

Raising covers a few inches above plants allows air to flow while still blocking direct rain contact.

Mulching around plants prevents mud from splashing onto lower leaves during heavy downpours.

Spacing plants farther apart than summer recommendations improves air movement and helps leaves dry faster between storms.

Checking plants regularly for signs of disease allows gardeners to remove affected leaves before problems spread.

Choosing disease-resistant varieties adds another layer of protection against common winter fungal issues.

Oregon’s wet winters require different strategies than cold, dry climates where snow is the main concern.

Understanding this unique challenge helps gardeners focus their efforts on the protection methods that actually matter most.

Accepting Slower Growth Instead Of Forcing Fertilizer

Winter brings shorter days and weaker sunlight that naturally slow down plant growth no matter what gardeners do.

Greens simply cannot photosynthesize as efficiently with only eight or nine hours of weak winter daylight.

Pushing plants with heavy fertilizer applications during this time often does more harm than good.

Excess nitrogen encourages soft, weak growth that frost damages easily and pests find irresistible.

Over-fertilized plants also become more susceptible to diseases because their tissues are less dense and more vulnerable.

Accepting that winter greens grow slowly allows plants to develop strong, healthy leaves at a natural pace.

A light application of compost in fall provides enough nutrients to support steady growth without forcing plants.

Patience becomes the most important tool in a winter gardener’s toolkit during these quiet months.

Greens may take two or three times longer to reach harvest size in winter compared to summer.

This slower growth actually concentrates sugars and flavors, making winter greens taste sweeter and more delicious.

Gardeners who embrace the natural rhythm of winter gardening enjoy better quality harvests without constant intervention.

Plants that grow at their own pace develop stronger root systems and better cold tolerance overall.

Trusting the process and resisting the urge to over-fertilize leads to healthier plants and more satisfying results throughout winter.