These 9 Aggressive Plants Could Cause Trouble In Oregon Yards

Some plants look beautiful and harmless at first, but in Oregon yards, a few can turn into serious troublemakers. Their fast growth, spreading roots, or invasive habits can take over gardens before you even notice.

A plant that seemed perfect quickly crowded out neighbors, damaged structures, or choked out other plants. Once aggressive plants get established, they’re hard to control and even harder to remove.

Oregon’s wet winters and mild summers make it easier for certain species to spread rapidly. Choosing the wrong plant can lead to extra work, unexpected costs, and frustration.

These aggressive plants are worth knowing about. Avoiding them helps protect your garden, keeps maintenance manageable, and ensures your yard stays beautiful without constant battles.

1. Himalayan Blackberry (Rubus armeniacus)

You notice a few wild berry canes along your back fence one spring, and by midsummer, they’ve formed an impenetrable thicket taller than you are. This scenario plays out in countless Oregon yards every year.

Himalayan blackberry is one of the most aggressive plants in the Pacific Northwest, and it spreads faster than almost anything else you’ll encounter.

The berries might be tasty, but the plant’s growth habits make it a nightmare for homeowners. Each cane can grow over 20 feet in a single season, arching over and rooting wherever it touches the ground.

Birds eat the berries and spread seeds everywhere, creating new patches in places you’d never expect. The thorny canes tear at clothing and skin, making removal painful work.

Many folks think they can manage a small patch for fresh berries, but that’s rarely how it goes. Within a couple of years, the brambles have taken over flower beds, climbed trees, and pushed into neighboring properties.

Oregon’s mild, wet climate provides perfect conditions for this plant to thrive year-round.

Getting rid of Himalayan blackberry requires persistence. Cut canes to the ground, then dig out the crown and root system.

You’ll probably need to repeat this process several times. Covering cleared areas with thick mulch or landscape fabric helps prevent new shoots.

Consider planting native trailing blackberry or thimbleberry instead, they produce fruit without the aggressive takeover.

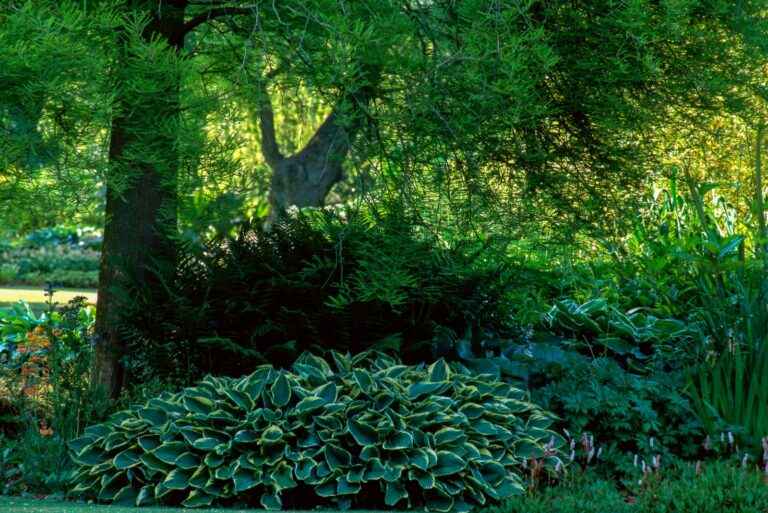

2. English Ivy (Hedera helix)

That charming green carpet climbing your backyard tree looks innocent enough at first. English ivy has been a popular groundcover and decorative vine for decades, planted intentionally by homeowners who appreciate its evergreen foliage.

But this European import has a dark side that reveals itself slowly, then all at once.

English ivy spreads through both runners along the ground and climbing vines that attach to any vertical surface. Those aerial roots damage tree bark, blocking sunlight and moisture that the tree needs to survive.

On buildings, the roots work their way into mortar and siding, causing expensive structural damage over time. Once established, ivy creates dense mats that smother native plants and prevent new seedlings from taking root.

The biggest mistake gardeners make is thinking they can keep it contained. Ivy produces seeds that birds distribute widely, and even small root fragments left in the soil can sprout new plants.

Oregon’s damp climate and mild winters mean ivy grows vigorously nearly year-round, making it particularly troublesome here.

Remove ivy by cutting vines at the base and carefully pulling them away from trees and structures. Dig out root systems thoroughly, checking back frequently for new growth.

Bag and dispose of all plant material, don’t compost it. Native options like inside-out flower or wild ginger provide beautiful groundcover without the invasion risk.

3. Scotch Broom (Cytisus scoparius)

Driving through Oregon in late spring, you’ll see hillsides covered in cheerful yellow blooms. Scotch broom puts on quite a show, and that’s exactly the problem.

This shrub was originally brought from Europe as an ornamental, but it has become one of Oregon’s most widespread invasive plants, colonizing roadsides, clear-cuts, and unfortunately, residential properties.

Each plant produces thousands of seeds that can remain viable in the soil for decades. The seed pods literally explode when ripe, flinging seeds up to 15 feet away.

Seeds also stick to shoes, pet fur, and vehicle tires, hitching rides to new locations. Scotch broom grows quickly, reaching six feet or taller, and its dense growth shades out native plants and garden favorites alike.

Some homeowners plant it deliberately for erosion control or privacy screening, not realizing what they’re unleashing.

The shrub fixes nitrogen in the soil, which sounds beneficial but actually changes soil chemistry in ways that favor more broom and other invasive species.

Fire danger increases significantly too, since the dried plants burn hot and fast.

Young plants can be pulled by hand when soil is moist, but you need to get the entire root system. Older shrubs require cutting at ground level, followed by careful monitoring for resprouts.

Cutting before seed set prevents spread. Native options like oceanspray or red-flowering currant provide beautiful blooms without the ecological damage.

4. Japanese Knotweed (Reynoutria japonica)

Your neighbor mentions a bamboo-like plant growing near their garage, and you walk over to take a look. What you find is actually Japanese knotweed, and it’s far worse than bamboo.

This plant has earned a fearsome reputation worldwide for its ability to damage foundations, crack pavement, and push through asphalt with alarming force.

Japanese knotweed grows from an extensive underground rhizome network that can spread 20 feet horizontally and burrow seven feet deep. Shoots emerge in spring and can grow four inches per day, quickly reaching 10 feet tall.

The hollow stems resemble bamboo, with heart-shaped leaves and small white flowers in late summer. Even tiny rhizome fragments can generate new plants, making it incredibly difficult to eliminate.

People sometimes plant it thinking they’re getting an attractive privacy screen or bamboo alternative. That decision typically leads to years of regret and expensive removal efforts.

The rhizomes can travel under property lines, causing disputes with neighbors. They damage drainage systems, water lines, and building foundations, leading to costly repairs.

Professional removal often becomes necessary because DIY methods frequently fail. Cutting stems only encourages more growth.

Digging requires removing all rhizome material to significant depth, missing even small pieces means the plant returns. Chemical treatment may be needed, applied carefully over multiple growing seasons.

Whatever you do, don’t plant Japanese knotweed. There are no good native alternatives because nothing else behaves this aggressively.

5. Tree-of-Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

A strange tree appears in your backyard seemingly overnight, growing faster than anything else around it. Tree-of-heaven lives up to its rapid-growth reputation, and despite the heavenly name, this plant causes earthly problems for Oregon homeowners.

The tree was imported from China in the 1800s and has been spreading aggressively ever since.

Tree-of-heaven produces thousands of winged seeds that disperse widely in the wind. The tree also spreads through root suckers that can emerge 50 feet or more from the parent tree, popping up through pavement, in flower beds, and anywhere else they choose.

Crushing the leaves releases a distinctive smell often compared to rancid peanut butter, definitely not pleasant. The roots produce chemicals that inhibit the growth of nearby plants, giving the tree a competitive advantage.

Some people mistake it for a native tree or even a walnut tree and let it grow. That’s a costly error.

Tree-of-heaven damages sidewalks and foundations with aggressive roots, drops massive amounts of seeds, and creates dense shade that kills grass and garden plants. The wood is weak and brittle, making large trees hazardous during storms.

Small seedlings can be pulled when the soil is moist, but you need to get the entire taproot. Larger trees require cutting followed by immediate treatment of the stump to prevent resprouting.

Watch for root suckers and remove them promptly. Native Oregon ash or bigleaf maple make far better shade trees for your yard.

6. Running Bamboo (Phyllostachys species)

Your friend installed a beautiful bamboo screen five years ago, and now it’s popping up in their driveway, pushing against the house foundation, and invading three neighboring yards. Running bamboo creates these scenarios regularly in Oregon communities.

While clumping bamboo varieties stay put, running types spread through underground rhizomes that travel surprising distances.

The rhizomes grow horizontally just below the soil surface, sending up new shoots throughout the growing season. In Oregon’s mild climate, running bamboo can spread several feet per year, and the rhizomes are tough enough to crack concrete and push through barriers.

Shoots emerge with incredible force, sometimes punching through asphalt or lifting patio pavers. Once established, the grove becomes nearly impossible to remove without serious effort.

Many homeowners choose running bamboo for quick privacy screening or an Asian garden aesthetic, not understanding the containment challenge. Even with barriers, rhizomes often find ways over, under, or through them.

The dense growth shades out everything else, and fallen leaves create a thick mat that prevents other plants from growing.

Containment requires installing rhizome barriers at least 30 inches deep, with the top edge protruding above ground. Check regularly for rhizomes trying to escape.

Removal means digging out the entire rhizome network, exhausting work that often takes multiple attempts. Consider clumping bamboo varieties instead, or choose native options like red-osier dogwood for screening that stays where you plant it.

7. Periwinkle / Vinca (Vinca minor)

The previous owners planted periwinkle as a low-maintenance groundcover under your trees, and now it’s everywhere.

This evergreen vine with pretty purple flowers seems harmless at first glance, but periwinkle has aggressive tendencies that become clear over time.

It spreads relentlessly through Oregon yards, smothering native plants and preventing tree seedlings from establishing.

Periwinkle grows through trailing stems that root at every node where they touch soil. A single plant can spread several feet in one season, forming dense mats that exclude almost everything else.

The thick coverage blocks light from reaching the ground, preventing native wildflowers and other plants from growing. In forested areas, periwinkle can carpet the entire understory, eliminating habitat for native insects and small animals.

Gardeners often choose it because it tolerates shade and requires little care. That low-maintenance quality comes from the plant’s aggressive nature, it outcompetes everything else, so you don’t need to weed.

Unfortunately, that same trait makes it problematic when it escapes into natural areas or spreads beyond where you want it.

Remove periwinkle by pulling up all the trailing stems and digging out root systems. This takes patience because you need to get every piece, leftover stem fragments will reroot.

Check the area regularly for several months afterward. Mulching heavily after removal helps prevent reinfestation.

Native options like kinnikinnick or wild strawberry provide attractive groundcover that supports local ecosystems rather than harming them.

8. Yellow Archangel (Lamium galeobdolon)

You receive a gift of pretty variegated groundcover from a neighbor who has plenty to share. Yellow archangel looks attractive in the pot, with silvery leaves and cheerful yellow flowers.

But accepting this gift might be a mistake you’ll spend years trying to fix. This European native has become a significant invasive problem in Oregon, particularly in forested areas and shady yards.

The plant spreads through stems that root at nodes, similar to periwinkle but even more aggressive. Yellow archangel also produces seeds and can spread through stem fragments, even small pieces left on the ground can take root.

It forms dense mats that smother native forest floor plants like trilliums and ferns. Oregon’s cool, moist climate provides ideal conditions for this plant to thrive and spread rapidly.

Many gardeners plant yellow archangel intentionally as a shade groundcover, attracted by the variegated foliage and bright flowers. Nurseries sometimes still sell it, though awareness of its invasive nature is growing.

The plant escapes cultivation easily, spreading into natural areas where it causes ecological damage by displacing native species.

Hand-pulling works for small infestations, but you need to remove all stems and roots. Bag the plant material rather than composting it, since stem fragments can root in your compost pile.

Persistent monitoring and removal of new growth will be necessary. Native alternatives like inside-out flower, foamflower, or piggyback plant provide beautiful shade groundcover without the invasion headaches.

9. Butterfly Bush (Buddleja davidii)

Butterflies love it, garden centers sell it, and it seems like the perfect addition to your pollinator garden. Butterfly bush has a complicated reputation in Oregon.

While it attracts butterflies with abundant nectar, it provides little else for pollinators and spreads aggressively into natural areas. The plant is actually listed as an invasive species in Oregon, though newer sterile cultivars are available.

Each flower spike produces thousands of tiny seeds that disperse widely in the wind. Seedlings pop up in surprising places, along roadsides, in gravel driveways, between patio stones, and in wild areas.

The shrubs grow quickly, reaching 10 feet or more, and can resprout from roots even after cutting. Butterfly bush colonizes riverbanks and disturbed areas, crowding out native plants that provide better support for native butterflies and other wildlife.

The butterfly attraction leads many well-meaning gardeners to plant it, not realizing the ecological tradeoffs. While adult butterflies visit for nectar, their caterpillars can’t eat the foliage, they need native host plants instead.

So butterfly bush offers a snack but not a complete habitat. The plants also self-seed prolifically in Oregon’s climate, creating management problems.

If you have butterfly bush, deadhead flowers before they set seed to prevent spread. Better yet, replace it with native alternatives that support the complete butterfly lifecycle.

Oceanspray, red-flowering currant, and Oregon grape provide nectar while also serving as host plants for native butterfly species. These choices create truly beneficial pollinator habitat without the invasive concerns.