These Plants Are Illegal To Have In Pennsylvania

A beautiful plant can be tempting, especially when it grows fast and fills empty spaces with lush greenery. Many gardeners bring home new plants without thinking twice, focusing only on how they look or how quickly they spread.

In Pennsylvania, though, not every plant is welcome. Some species are actually illegal to grow, sell, or even keep in your yard.

These restricted plants often spread aggressively and push out native vegetation that local wildlife depends on. Over time, they can damage natural habitats, disrupt soil balance, and become difficult to control.

What starts as a simple garden addition can quickly turn into a serious environmental problem.

Knowing which plants are banned helps you avoid fines and protect Pennsylvania’s landscapes.

With the right awareness, you can make responsible choices, support native ecosystems, and keep your garden both beautiful and lawful without unexpected trouble later on.

1. Giant Hogweed

Giant hogweed stands as one of the most dangerous plants you can encounter in Pennsylvania. This massive plant can grow up to 14 feet tall with leaves that spread over five feet wide. The white flowers form umbrella shapes that can measure two feet across.

What makes this plant truly scary is its clear, watery sap. When the sap touches your skin and you go into sunlight, it causes painful burns and blisters that can last for months. The burns can be so bad that they leave permanent scars and dark spots on your skin.

Pennsylvania law treats giant hogweed very seriously. It’s listed as both a federal and state noxious weed, which means you cannot grow it, sell it, or move it anywhere.

If you see this plant on your property or anywhere in Pennsylvania, you must report it to the authorities right away.

The plant originally came from Asia and was brought to America as a decorative garden plant. People thought it looked impressive because of its huge size. Now it spreads along streams, roads, and forests throughout Pennsylvania.

Getting rid of giant hogweed requires professional help because of the danger it poses. You should never try to cut it down or touch it yourself.

Always wear protective clothing and eye protection if you must be near it. The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture tracks all sightings and works to remove these dangerous plants before they spread further.

2. Japanese Knotweed

Property owners in Pennsylvania face a nightmare when Japanese knotweed shows up on their land. This aggressive plant looks somewhat like bamboo with hollow stems that can reach 10 feet high. The heart-shaped leaves grow in a zigzag pattern along the stems.

The real trouble starts underground where you cannot see it. Japanese knotweed sends out roots called rhizomes that spread up to 20 feet in all directions.

These tough roots can punch through concrete, damage building foundations, and crack driveways and sidewalks.

Pennsylvania made it against the law to sell or give away Japanese knotweed because it causes so much damage. The plant spreads incredibly fast and takes over areas where native plants should grow.

It also makes problems worse along streams and rivers by pushing out plants that hold soil in place.

Once Japanese knotweed gets established on your property, removing it becomes extremely difficult and expensive. The roots go down 10 feet deep into the ground. Even a tiny piece of root left behind can grow into a whole new plant.

Some people in Pennsylvania have spent thousands of dollars trying to get rid of this invasive species. It can take three to five years of treatment to completely remove it.

The plant grows back quickly if you miss even one small section of root. Many banks now refuse to give home loans for properties with Japanese knotweed because it lowers property values so much.

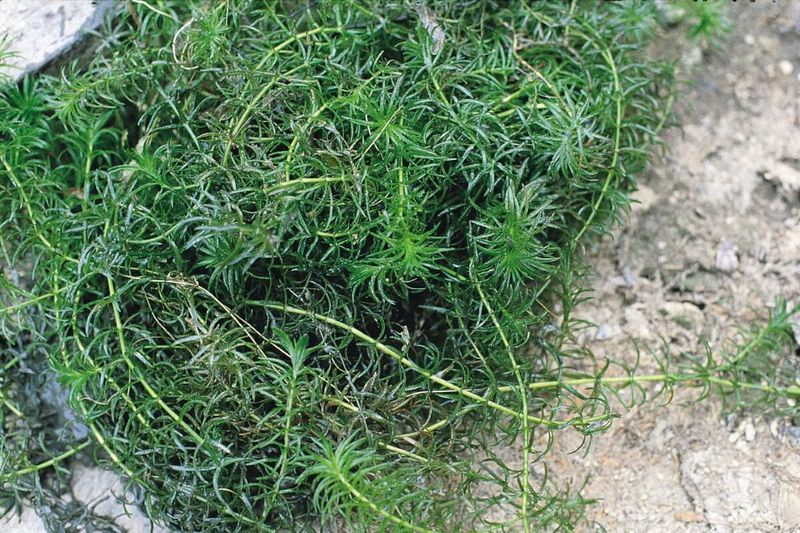

3. Mile-A-Minute Vine

Mile-a-minute vine earned its name by growing incredibly fast across Pennsylvania landscapes. This climbing plant can grow six inches in a single day during the summer months.

The vine has distinctive triangle-shaped leaves and small curved thorns that help it climb over everything in its path.

Pennsylvania classified this plant as a noxious weed because of how quickly it smothers native plants and trees. The vine forms thick blankets that block sunlight from reaching plants underneath.

Trees and shrubs cannot get the light they need when mile-a-minute covers them completely.

The vine came to Pennsylvania from Asia in the 1930s, likely in contaminated seed shipments. Since then, it has spread throughout the state, especially in areas with disturbed soil.

Construction sites, forest edges, and stream banks provide perfect growing conditions for this invasive pest.

Young plants produce small white flowers that turn into dark blue berries by late summer. Each berry contains a single seed, and one plant can make thousands of seeds in a season. Birds eat the berries and spread the seeds all over Pennsylvania through their droppings.

The state takes the threat seriously enough to make it unlawful to grow, sell, or transport mile-a-minute vine. Forest managers and conservation workers spend significant time and money trying to control its spread.

Early detection helps because young plants are easier to remove than established vines. If you spot this fast-growing menace in Pennsylvania, you should report it to local environmental authorities immediately.

4. Hydrilla

Pennsylvania’s lakes and waterways face a serious threat from hydrilla, an underwater plant that grows out of control. This aquatic invader forms thick mats beneath the water surface that can grow up to 25 feet long.

The plant has small, pointed leaves that grow in groups of five around the stem.

State law makes it completely against the rules to possess, transport, or put hydrilla into any Pennsylvania waters. The plant spreads so easily that even a tiny fragment can start a new colony.

It reproduces through pieces that break off, special underground tubers, and seeds that can survive for years.

Hydrilla clogs up lakes, ponds, and slow-moving streams throughout areas where it takes hold. The dense growth makes swimming, fishing, and boating nearly impossible.

Water cannot flow properly through areas choked with hydrilla, which can lead to flooding problems.

The plant originally came from Asia and was sold in aquarium stores as a decorative plant for fish tanks. People dumped their aquarium water into local waterways, and hydrilla escaped into Pennsylvania’s natural water systems.

Now it competes with native underwater plants that fish and other water animals depend on for food and shelter.

Getting hydrilla out of a lake costs enormous amounts of money and requires years of effort. Treatment methods include special chemicals, mechanical harvesting, and introducing plant-eating insects.

Pennsylvania authorities monitor water bodies carefully to catch new infestations early. Boat owners must clean their vessels thoroughly when moving between different water bodies to avoid spreading this troublesome plant.

5. Purple Loosestrife

Wetlands across Pennsylvania once hosted a beautiful but destructive invader called purple loosestrife.

This plant grows tall spikes covered in bright magenta-purple flowers that catch your eye from far away. Each plant can reach six feet in height and produce millions of tiny seeds every year.

The flowers might look pretty, but purple loosestrife causes major problems in Pennsylvania’s wetlands and marshes.

It pushes out native plants that ducks, geese, and other wildlife need for food and nesting. One purple loosestrife plant can take over an entire wetland area within just a few years.

Pennsylvania restricts the sale of purple loosestrife because of the damage it causes to natural areas.

Garden centers cannot sell it, and people cannot give it away or plant it on their property. The state wants to stop this plant from spreading to any more wetland areas.

People originally brought purple loosestrife from Europe to use in gardens and for making medicine. The plant escaped from gardens and found Pennsylvania’s wetlands to be perfect growing conditions.

Without natural enemies to keep it under control, purple loosestrife spread rapidly throughout the state.

Each flower spike produces up to 300,000 seeds that spread through wind, water, and on the feet of birds and animals. The seeds can stay alive in soil for years, waiting for the right conditions to sprout.

Pennsylvania’s environmental agencies work hard to remove purple loosestrife from protected wetlands and teach people about the problems it creates for native ecosystems and wildlife habitats.

6. Tree-Of-Heaven

Pennsylvania declared war on tree-of-heaven when it became linked to the spotted lanternfly invasion. This fast-growing tree can shoot up 10 feet in a single year and reach heights of 80 feet. The leaves grow in long rows with 10 to 40 small leaflets on each stem.

The tree earned its place on Pennsylvania’s noxious weed list because it serves as the favorite host plant for spotted lanternflies. These destructive insects prefer to lay their eggs on tree-of-heaven bark.

The tree actually produces chemicals that help the lanternfly bugs survive and multiply across the state.

State regulations now make it against the law to grow or sell tree-of-heaven anywhere in Pennsylvania.

Property owners must remove these trees from their land to help control the spotted lanternfly population. The tree spreads through seeds and also sends up shoots from its roots.

Tree-of-heaven came from China in the 1700s when people thought it would make a good shade tree for cities. It grows in poor soil and polluted areas where other trees struggle.

This toughness helped it spread throughout Pennsylvania, especially in cities and along highways.

The tree gives off a strong smell that many people compare to rancid peanut butter or cat urine. Cutting down tree-of-heaven requires careful planning because the stumps send up many new shoots.

The roots must be treated with special chemicals to stop regrowth. Pennsylvania residents should learn to identify this tree and report large stands to local authorities for proper removal and disposal.

7. Kudzu

Kudzu has earned the nickname “the vine that ate the South,” and Pennsylvania wants to keep it from eating the Keystone State too.

This aggressive climber can grow one foot per day during peak summer weather. The large leaves grow in groups of three and can measure up to six inches across.

The vine climbs over everything it touches, including trees, buildings, telephone poles, and even cars that sit still too long. Kudzu blocks out all sunlight to plants underneath its thick blanket of leaves.

Trees covered by kudzu cannot make food through their leaves and eventually become weakened.

Pennsylvania classified kudzu as a noxious weed, making it against the law to grow or spread this plant anywhere in the state. The vine arrived in America from Japan in the 1800s and was later promoted as a way to control soil erosion.

That plan backfired badly when kudzu started taking over entire forests. A single kudzu plant can cover an acre of land in a short time. The roots grow deep and can weigh up to 400 pounds.

These massive roots store energy that helps the plant survive cold Pennsylvania winters and come back even stronger the next spring.

Getting rid of kudzu takes years of persistent effort and costs thousands of dollars per acre. The vine grows back from any root pieces left in the ground.

Pennsylvania environmental workers stay alert for any kudzu sightings because early removal prevents the vine from becoming established and causing widespread damage to forests, farms, and communities throughout the state.