These Trees In South Carolina Could Get You Fined If You Don’t Remove Them

Not all trees are safe to keep in your South Carolina yard. Certain species are considered hazardous, invasive, or a public safety risk, and local laws require homeowners to remove them.

Failing to comply can result in fines or mandatory removal at your expense. One tree in the wrong place can quickly become a costly problem. These trees may drop large limbs, damage foundations or sidewalks, or pose fire hazards.

Municipalities enforce removal to protect people, property, and neighborhoods. Knowing which trees fall into this category helps homeowners act proactively and avoid fines or legal trouble.

Removing dangerous trees early keeps your property safe and compliant. South Carolina homeowners who follow these guidelines protect their landscape, their investment, and their neighborhood. Manage trees wisely to stay safe and legal.

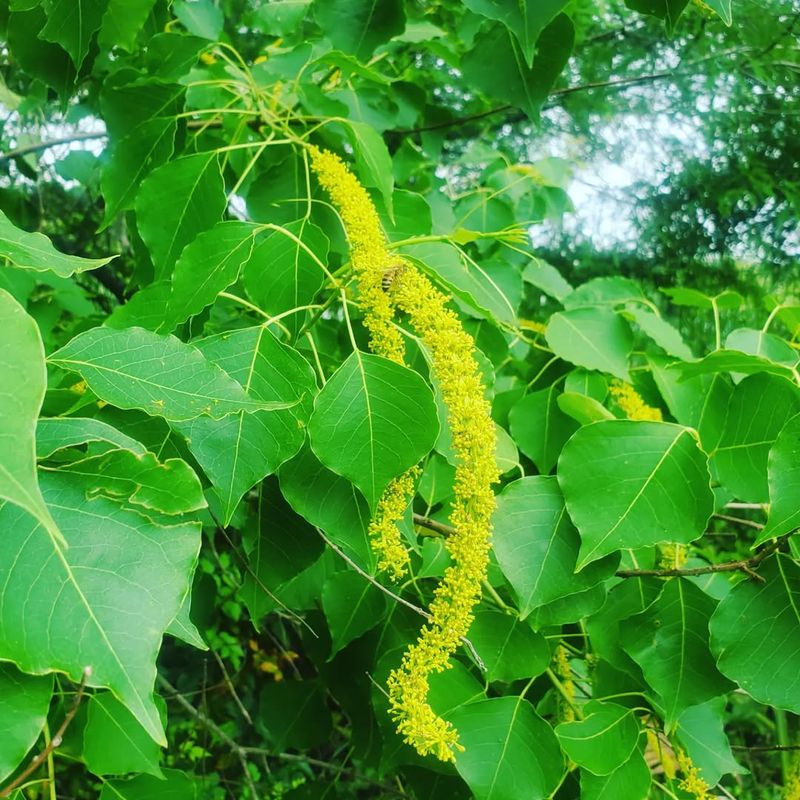

Tree Of Heaven (Ailanthus Altissima)

Known for its deceptive name, this Asian import has become one of the most aggressive invaders across South Carolina’s urban and rural landscapes.

Its rapid growth rate and ability to thrive in poor soil conditions make it seem like an ideal tree at first glance, but the reality is far more problematic for property owners.

Many municipalities have begun requiring removal on managed properties due to the extensive damage this species causes over time.

Root suckering is perhaps the most troublesome characteristic of this invasive tree, with underground shoots spreading dozens of feet from the parent trunk.

A single tree can quickly become a dense grove that overwhelms gardens, cracks foundations, and damages sidewalks and driveways.

The aggressive root system seeks out water lines and sewer pipes, causing expensive infrastructure repairs for unsuspecting homeowners.

South Carolina counties with strict invasive species regulations often target this tree specifically because of its ability to outcompete native vegetation.

The tree produces thousands of wind-dispersed seeds annually, allowing it to colonize disturbed areas, forest edges, and abandoned lots with remarkable speed.

Property managers who fail to control or remove established specimens may face citations and fines from local code enforcement.

Beyond structural damage, the tree releases chemicals that inhibit the growth of surrounding plants, creating barren zones beneath its canopy.

This allelopathic effect makes landscaping nearly impossible and reduces property values significantly over time.

Chinese Tallow Tree (Triadica Sebifera)

Autumn brings a spectacular display of red, orange, and yellow foliage to this ornamental tree, which is exactly why it was originally introduced to Southern landscapes decades ago.

However, beneath that beautiful exterior lies one of the most serious threats to South Carolina’s native forests and wetland ecosystems.

What starts as a single decorative specimen can transform into an ecological disaster that displaces centuries-old native plant communities.

Wetlands throughout the coastal regions of South Carolina have experienced dramatic changes due to Chinese tallow invasions, with dense thickets replacing diverse native vegetation.

The tree produces waxy seeds that birds readily consume and distribute across vast distances, allowing rapid colonization of new areas. Each mature tree can generate tens of thousands of seeds annually, creating a seed bank that persists in soil for years.

Land managers and homeowners associations have begun mandating removal because of the tree’s classification as a highly invasive species by state environmental agencies.

Properties located near protected natural areas or conservation easements face particularly strict enforcement, with fines imposed on owners who allow the tree to spread unchecked.

The financial penalties can escalate quickly if seeds from your property invade neighboring lands or public spaces. Forest edges, abandoned fields, and disturbed sites become rapidly dominated by Chinese tallow, which tolerates both flooding and drought conditions.

Its adaptability makes eradication efforts challenging and expensive once established populations take hold.

Mimosa / Silk Tree (Albizia Julibrissin)

Those fluffy pink blooms and delicate fern-like leaves might charm gardeners initially, but this Asian ornamental has earned a spot on numerous county invasive plant watchlists throughout South Carolina.

Originally planted for its exotic appearance and fast shade production, the mimosa has proven itself to be an aggressive colonizer that escapes cultivation with alarming ease.

Property owners near streams and waterways face particular scrutiny from environmental authorities regarding this species.

Streambank stabilization efforts are constantly undermined by mimosa’s tendency to spread along waterways, where its shallow root system actually increases erosion rather than preventing it.

The tree produces enormous quantities of seeds contained in flat pods that float downstream, establishing new populations miles from the original planting site.

Each tree can generate thousands of viable seeds that remain dormant in soil for extended periods, complicating eradication efforts.

Fast seeding behavior means that a single mimosa can populate an entire neighborhood within just a few growing seasons, creating headaches for community associations and municipal planners.

Many South Carolina counties have added enforcement language to their nuisance plant ordinances specifically targeting this species. Homeowners who ignore removal notices may face escalating fines and potential legal action from local authorities.

Forest openings, roadsides, and disturbed areas become quickly dominated by dense mimosa thickets that exclude native vegetation and reduce wildlife habitat quality.

The tree’s nitrogen-fixing ability actually alters soil chemistry in ways that favor additional invasive species establishment.

Callery Pear (Bradford Pear And Related Cultivars)

Shopping centers, parking lots, and suburban streets across South Carolina became lined with these white-flowering trees during the 1980s and 1990s, creating what seemed like perfect ornamental landscapes.

Fast forward to today, and state officials have launched a comprehensive initiative discouraging new plantings while actively encouraging removal of existing specimens.

The dramatic shift in policy reflects growing recognition of serious ecological and safety problems associated with all Callery pear cultivars.

Weak branch structure creates hazardous conditions during storms, with major limbs frequently splitting from trunks and crashing onto vehicles, buildings, and power lines.

Insurance companies have documented increasing property damage claims related to Bradford pear failures, prompting some municipalities to require removal from properties near public infrastructure.

The structural problems worsen as trees age, making older specimens particularly dangerous during severe weather events.

Natural areas throughout South Carolina now face invasion by Callery pear thickets that form impenetrable barriers excluding native plants and wildlife.

Different cultivars cross-pollinate to produce thorny, aggressive offspring that spread rapidly into forests, fields, and along roadsways.

Local replacement incentive programs offer free native trees to homeowners who remove Bradford pears, making compliance more affordable.

State forestry officials have classified Callery pears as a priority invasive species requiring active management on public and private lands.

Property owners who refuse voluntary removal may eventually face mandatory compliance as local ordinances continue strengthening regulations against this problematic tree.

Chinaberry Tree (Melia Azedarach)

Grandparents might remember when this tree was deliberately planted near farmhouses for quick shade and its clusters of lavender flowers that perfume spring air.

Times have changed dramatically, and modern environmental science has revealed the serious ecological damage caused by this seemingly harmless ornamental.

South Carolina municipalities increasingly treat Chinaberry as a regulated nuisance species, with property owners facing potential citations for allowing unchecked growth and spread.

Forest edges and disturbed sites become rapidly colonized by Chinaberry seedlings that grow with remarkable speed, reaching reproductive maturity within just a few years.

Birds consume the yellow berries and distribute seeds across wide areas, creating new infestations far from parent trees. The tree’s ability to resprout vigorously from cut stumps makes eradication challenging without proper herbicide treatment following removal.

Invasive classification by state environmental agencies reflects concerns about Chinaberry’s displacement of native species and its formation of dense stands that reduce biodiversity.

Properties adjacent to conservation lands or protected natural areas face stricter enforcement regarding this species, with fines imposed on owners who allow seed dispersal into sensitive habitats.

Some homeowners associations have added Chinaberry to prohibited species lists, requiring removal as a condition of property ownership.

The tree’s tolerance of poor soil and drought conditions allows it to thrive in abandoned lots and neglected properties, where it can become a code enforcement issue.

Municipal authorities may require removal and charge cleanup costs to property owners who fail to comply with notices.

Paper Mulberry (Broussonetia Papyrifera)

Allergy sufferers know this tree all too well, as its prodigious pollen production creates miserable conditions throughout South Carolina communities during spring months.

Originally introduced for its fast growth and supposed erosion control properties, Paper Mulberry has instead become a spreading nightmare that reproduces through both seeds and aggressive root shoots.

Some cities have enacted specific restrictions on planting this species due to public health concerns and its invasive tendencies.

Root shoots can emerge dozens of feet from the parent tree, creating dense colonies that overwhelm gardens, lawns, and natural areas with surprising speed.

Attempting to control the spread through mowing or cutting only stimulates more vigorous suckering, making the problem worse without proper herbicide application.

Property owners who allow Paper Mulberry to spread onto neighboring lands may face liability for damages and cleanup costs.

Male trees produce enormous quantities of highly allergenic pollen that triggers severe respiratory reactions in sensitive individuals, creating nuisance conditions that affect entire neighborhoods.

Municipal health departments have documented complaints about Paper Mulberry pollen, leading some jurisdictions to classify it as a public health hazard requiring removal.

Homeowners associations increasingly mandate removal to protect community members from allergy triggers. The tree’s ability to thrive in urban environments and disturbed soils means it spreads readily along roadsides, in vacant lots, and through neglected properties.

Code enforcement officials may require removal as part of property maintenance standards, with fines imposed for non-compliance.

Princess Tree / Royal Paulownia (Paulownia Tomentosa)

Rapid growth that can exceed ten feet in a single season makes this Asian import seem like a miracle solution for instant shade and privacy screening.

However, that same explosive growth rate has transformed Princess Tree into an ecological problem requiring active monitoring and control efforts by South Carolina state agencies.

Roadsides and forest openings throughout the state now host unwanted Paulownia populations that originated from ornamental plantings decades ago.

Each mature tree produces millions of tiny seeds that disperse on wind currents across vast distances, colonizing disturbed sites, clearcuts, and abandoned properties with remarkable efficiency.

The seeds require bare soil and sunlight to germinate, which is why the tree thrives along roadsides, in logging areas, and wherever vegetation has been cleared.

Property owners near these disturbed areas may find their land invaded by Paulownia seedlings seemingly overnight.

State monitoring efforts focus on preventing Princess Tree from establishing permanent populations in natural areas, where it can outcompete native vegetation and alter forest succession patterns.

Some counties have begun requiring removal from properties adjacent to public lands or conservation easements to prevent seed dispersal into protected areas.

Fines may be imposed on property owners who allow mature trees to produce seeds that invade neighboring properties or natural habitats.

The tree’s ability to resprout from roots and stumps makes eradication challenging without sustained management efforts combining cutting and herbicide treatment.

Municipal authorities may mandate professional removal to ensure complete eradication from problem properties.

Saltcedar / Tamarisk (Tamarix Species)

Western states have fought billion-dollar battles against Saltcedar infestations that drain rivers and destroy riparian ecosystems, and South Carolina officials are determined to prevent similar catastrophes from developing locally.

While the tree’s presence remains limited in the state, monitoring efforts focus on early detection and rapid response to prevent establishment of permanent populations.

Waterway management authorities regulate this species due to its extreme water consumption and ecosystem disruption potential.

Each mature Saltcedar can transpire hundreds of gallons of water daily, lowering water tables and reducing stream flows in ways that harm native vegetation and aquatic habitats.

The tree’s deep taproot accesses groundwater unavailable to most native plants, giving it a competitive advantage during drought conditions.

Properties near waterways face particular scrutiny regarding any Saltcedar presence, with mandatory removal requirements enforced by environmental agencies.

Dense thickets formed by Saltcedar exclude native riparian vegetation and reduce habitat quality for wildlife species dependent on diverse plant communities.

The tree’s tiny scale-like leaves and pink flower spikes might seem attractive, but the ecological damage far outweighs any ornamental value.

State agencies maintain watchlists of known Saltcedar locations and require property owners to eradicate any specimens discovered on their land.

Quarantine-style restrictions apply to properties where Saltcedar has been identified, with mandatory treatment and monitoring requirements imposed to prevent spread.

Failure to comply with removal orders can result in substantial fines and potential legal action from state environmental authorities.

Glossy Privet (Ligustrum Lucidum — Tree Form)

Hedge plantings seemed innocent enough when glossy privet first became popular in South Carolina landscapes, but the tree form has proven capable of escaping cultivation and forming dense forest invasions.

Clemson Extension has officially listed this species as invasive, reflecting growing concerns about its ecological impacts and aggressive spread patterns.

What starts as a tidy evergreen hedge can transform into towering trees that produce millions of bird-dispersed seeds annually.

Forest understories throughout South Carolina have experienced dramatic changes where glossy privet has invaded, with dense thickets replacing diverse native plant communities and reducing wildlife habitat quality.

The tree tolerates deep shade, allowing it to invade established forests where other invasive species cannot compete. Birds consume the dark purple berries and distribute seeds across wide areas, creating new infestations far from original plantings.

Homeowners associations and land management agencies increasingly require removal of tree-form glossy privet to prevent further ecological damage and seed production.

Properties adjacent to natural areas or conservation lands face stricter enforcement, with fines imposed on owners who allow privet to spread into protected habitats.

The tree’s evergreen nature means it continues photosynthesizing while native deciduous trees are dormant, giving it additional competitive advantages.

Eradication efforts prove challenging because glossy privet resprouts vigorously from cut stumps and produces new shoots from root fragments left in soil.

Professional removal with herbicide treatment is often required to achieve complete control, with municipal authorities sometimes mandating specific treatment protocols.

Brazilian Pepper Tree (Schinus Terebinthifolia — Restricted Import Species)

Florida’s experience with Brazilian Pepper has been nothing short of catastrophic, with millions of acres invaded by this aggressive species that forms impenetrable monocultures excluding all native vegetation.

South Carolina officials learned from their southern neighbor’s mistakes and enacted proactive regulations prohibiting sale, planting, and importation of this tree before it could establish permanent populations locally.

Quarantine-style restrictions apply even though the species remains rarely established within state boundaries.

Invasive risk warnings from state and federal agencies classify Brazilian Pepper as one of the most dangerous potential invaders for South Carolina’s climate and ecosystems.

The tree produces abundant red berries that birds readily consume and distribute, allowing rapid colonization of new areas once a seed source becomes established.

Each mature tree can generate thousands of seeds annually, creating persistent seed banks that complicate eradication efforts.

Property owners who somehow acquire Brazilian Pepper specimens face mandatory removal requirements and potential fines for possessing prohibited plant species.

State nursery inspection programs monitor for illegal sales, and retailers found offering Brazilian Pepper can face license suspension and substantial penalties.

The tree’s tolerance of salt spray and coastal conditions makes it particularly threatening to South Carolina’s valuable coastal ecosystems.

Early detection and rapid response protocols require immediate reporting and removal of any Brazilian Pepper trees discovered in the state.

Environmental agencies treat this species with the same urgency as agricultural quarantine pests, recognizing the catastrophic potential if populations become established.