These Plants Are Illegal To Have In Texas

Texas has strict laws about which plants you can grow in your yard or garden. Some plants might look pretty or seem harmless, but they can actually cause big problems for the environment.

These troublesome plants spread quickly and take over natural areas, pushing out native Texas plants that wildlife depends on. They can clog waterways, damage farmland, and cost millions of dollars to control.

The Texas Department of Agriculture keeps a list of plants that are illegal to own, sell, or grow anywhere in the state. Breaking these rules can lead to serious fines and legal trouble.

Whether you’re a gardener, landscaper, or just someone who loves plants, knowing which ones are banned in Texas is really important.

Some of these illegal plants were once sold in stores or used in gardens, so you might even have them growing on your property without realizing it.

Learning about these forbidden plants helps protect Texas ecosystems and keeps you on the right side of the law.

1. Alligatorweed (Alternanthera Philoxeroides)

Alligatorweed earned its name because it often grows in the same swampy areas where alligators live. This aggressive aquatic plant came to the United States from South America decades ago.

Now it’s one of the most problematic invasive plants in Texas waterways.

The plant has hollow stems that let it float on water surfaces. It forms thick mats that can completely cover ponds, lakes, and slow-moving streams.

These dense blankets block sunlight from reaching underwater plants and reduce oxygen levels that fish need to survive.

On land, alligatorweed spreads through garden beds and crop fields with surprising speed. Its roots grow deep and break into pieces easily.

Each tiny piece can sprout into a whole new plant. This makes it incredibly hard to remove once it takes hold in an area.

Texas law makes it illegal to possess, transport, or sell alligatorweed anywhere in the state. The penalties exist because this plant causes serious economic damage to agriculture and recreation.

It clogs irrigation systems and makes fishing or boating nearly impossible in affected waters.

Property owners who discover alligatorweed should contact their local Texas A&M AgriLife Extension office immediately. Professionals can help identify the plant correctly and suggest approved removal methods.

Never try to move or dispose of alligatorweed yourself, as fragments can establish new infestations downstream.

2. Giant Reed (Arundo Donax)

Giant reed looks like bamboo but grows even taller, sometimes reaching heights of 30 feet. This massive grass came from Asia and the Mediterranean region.

People originally planted it for erosion control and as windbreaks, not knowing the problems it would cause.

Along Texas rivers and streams, giant reed creates impenetrable walls of vegetation. These thick stands crowd out native plants that provide food and shelter for wildlife. Birds and other animals lose their natural habitats when giant reed takes over.

The plant’s root system is incredibly strong and spreads rapidly underground. A single stand can expand several feet in just one growing season.

During wildfires, giant reed burns intensely and helps flames spread faster than native plants would.

Water usage is another major concern with giant reed in Texas. Each plant drinks enormous amounts of water, much more than native vegetation.

In a state where water conservation matters greatly, this becomes a serious issue for rivers and aquifers.

Texas classifies giant reed as illegal to distribute, sell, or import. Existing stands should be reported to local authorities who can arrange proper removal.

Cutting it down doesn’t work because the roots just send up new shoots. Professional treatment requires special herbicides applied at specific times of year.

3. Field Bindweed (Convolvulus Arvensis)

Farmers across Texas know field bindweed as one of their worst nightmares. This creeping vine with pretty white or pink trumpet-shaped flowers might look innocent.

However, it destroys crops and gardens with relentless determination.

Field bindweed arrived in the United States as a contaminant in crop seeds during the 1800s. Since then, it has spread to nearly every state. Its roots can grow down 20 feet deep into the soil, making removal extremely difficult.

The vine twists around crop plants and pulls them down toward the ground. This smothering action reduces harvest yields significantly.

In Texas agricultural areas, field bindweed causes millions of dollars in lost production every single year.

Even tiny pieces of root left in the soil will sprout new plants. One plant can spread across an entire field in just a couple of growing seasons.

The seeds remain viable in soil for up to 50 years, waiting for the right conditions to germinate.

Texas law prohibits the sale, distribution, and importation of field bindweed. Landowners must take action to control existing infestations.

Repeated treatments over several years are usually necessary. Local county extension agents can provide guidance on legal control methods approved for use in Texas.

4. Japanese Dodder (Cuscuta Japonica)

Japanese dodder looks like someone threw orange spaghetti all over your plants. This bizarre parasitic plant has no leaves and produces no chlorophyll of its own. Instead, it wraps around host plants and steals their nutrients directly.

The thin, string-like stems wind tightly around stems and branches of other plants. Special structures called haustoria penetrate the host plant’s tissues.

Through these connections, dodder sucks out water, minerals, and sugars that the host plant worked hard to produce.

Plants attacked by Japanese dodder become weak and stunted. They produce fewer flowers and fruits.

In severe cases, the host plant becomes so weakened that it cannot recover, even if the dodder is removed.

This parasitic plant spreads through tiny seeds that can survive in soil for many years. Birds and water can carry the seeds to new locations.

Once dodder establishes itself in an area, it moves from plant to plant rapidly.

Texas prohibits possession and transport of Japanese dodder because it threatens agricultural crops and native plants. Ornamental gardens, vegetable plots, and natural areas all face risks from this parasite.

Anyone who spots the distinctive orange tangles should report it immediately to the Texas Department of Agriculture. Early detection makes control much easier and more effective.

5. Anchored Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia Azurea)

People sometimes confuse anchored water hyacinth with its more famous cousin, common water hyacinth. Both species cause major problems in Texas waterways.

Anchored water hyacinth actually roots in the bottom of shallow ponds and lakes rather than floating freely.

The plant produces beautiful purple flowers that attract attention from gardeners and pond owners. Those pretty blooms hide a destructive nature.

Dense colonies form quickly and block access to fishing spots and boat launches throughout Texas.

Unlike floating plants, anchored water hyacinth grows from roots stuck in the mud. This makes it harder to remove than free-floating species. The plants grow tall and thick, creating walls of vegetation that boats cannot pass through.

Fish populations suffer when anchored water hyacinth takes over. The dense growth reduces oxygen levels in the water.

It also blocks sunlight from reaching native underwater plants that fish depend on for food and shelter.

Texas made this plant illegal because it spreads so aggressively in warm climates. The state’s long growing season and numerous waterways provide perfect conditions for anchored water hyacinth.

Fragments break off easily and float downstream to start new colonies. Water birds can carry seeds on their feet to previously uninfested areas. Professional removal requires special equipment and approved aquatic herbicides.

6. Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum Salicaria)

Garden centers once sold purple loosestrife as an ornamental plant for wet areas. Those tall spikes covered in magenta flowers looked stunning in landscape designs.

Nobody realized at the time how much damage this European import would cause to Texas wetlands.

Each purple loosestrife plant produces up to 2.5 million seeds annually. Wind, water, animals, and people spread these tiny seeds far and wide. The seeds remain capable of sprouting for several years after they land in soil or water.

Wetlands invaded by purple loosestrife lose their diversity rapidly. Native plants that provide food for waterfowl and other wildlife get pushed out.

Ducks, geese, and other birds find less nutritious food options when purple loosestrife dominates an area.

The plant’s root system changes soil chemistry and water flow patterns in marshes. These changes make it even harder for native plants to compete.

Once purple loosestrife establishes itself, reversing the damage takes years of dedicated effort.

Texas banned purple loosestrife to protect valuable wetland ecosystems throughout the state. Even sterile cultivars remain illegal because they can still cross-pollinate with wild plants.

Gardeners who want similar-looking plants should choose native alternatives like blazing star or ironweed. These provide the same visual impact without threatening Texas natural areas.

7. Chinese Tallow Tree (Triadica Sebifera)

Chinese tallow tree was promoted for decades as a wonderful shade tree for Texas yards. Nurseries sold thousands of them.

The trees grow fast, tolerate poor soil, and display beautiful fall colors. These attractive qualities masked a serious invasive threat.

Birds love eating the waxy white seeds that Chinese tallow produces in huge quantities. After digesting the seeds, birds deposit them far from the parent tree.

This natural spreading mechanism helped Chinese tallow invade forests, prairies, and coastal areas across Texas.

Native tree seedlings cannot compete with Chinese tallow in many situations. The invasive tree grows faster and tolerates flooding better than most native species. Entire forests in East Texas have been transformed into Chinese tallow thickets.

The tree’s sap contains toxins that irritate human skin and can harm livestock. Dense stands create poor habitat for wildlife compared to native forests.

Many insects and animals that Texas ecosystems depend on cannot use Chinese tallow as a food source.

Texas now prohibits the sale, propagation, and distribution of Chinese tallow trees. Property owners with existing trees face difficult decisions.

Cutting them down releases thousands of seeds stored in the soil. Professional foresters recommend specific treatment plans that include herbicide application to prevent regrowth.

Replacing Chinese tallow with native Texas trees helps restore ecological balance.

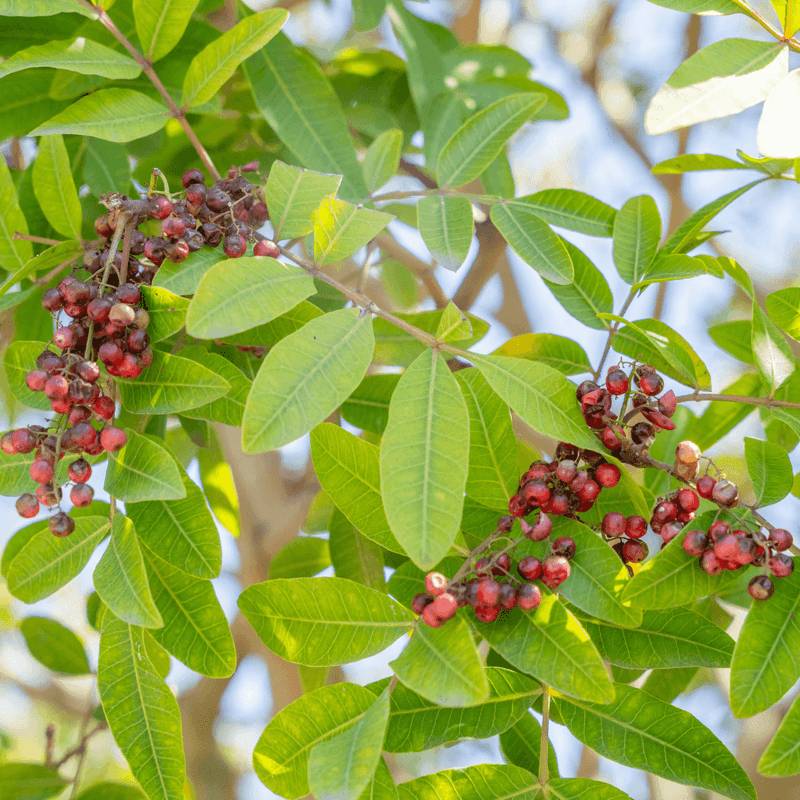

8. Brazilian Peppertree (Schinus Terebinthifolia)

Brazilian peppertree produces bright red berries that look festive during winter holidays. Florists once harvested the branches for decorative arrangements.

Landscapers planted the trees in South Texas because they tolerate salt spray and poor soil near the coast.

The tree spreads aggressively through seeds carried by birds and small mammals. Each tree produces thousands of berries annually. A single tree can create a dense thicket of offspring within just a few years.

People with allergies often react badly to Brazilian peppertree. The sap and crushed leaves release chemicals similar to poison ivy.

Sensitive individuals develop rashes, breathing problems, and eye irritation when near these trees.

Native plants struggle to survive where Brazilian peppertree takes hold. The invasive tree creates dense shade that blocks sunlight from reaching the ground. It also releases chemicals from its roots that inhibit the growth of nearby plants.

Texas classified Brazilian peppertree as illegal because it threatens coastal ecosystems and natural areas. The tree has invaded wildlife refuges, parks, and private lands across South Texas.

Removal requires cutting the tree and treating the stump immediately with approved herbicides. Seeds in the soil can sprout for years after adult trees are removed.

Long-term monitoring and follow-up treatments ensure that Brazilian peppertree doesn’t return to reclaim the area.