11 Common Florida Garden Pests And How To Stop Them Naturally

Florida gardens never really sleep. Tomatoes ripen in winter, citrus trees stay green year-round, and backyard beds keep producing long after gardeners up north pack it in.

Unfortunately, insects and critters love this nonstop growing season just as much as the plants do. One week your garden looks perfect, the next week leaves are full of holes, flowers look distorted, or sticky residue coats everything in sight.

It is frustrating when pests seem to appear overnight and multiply faster than you can react.

The good news is that most Florida garden pests can be controlled without harsh chemicals or expensive treatments.

When you catch problems early, it becomes much easier to get things under control before your garden starts suffering. With the right mix of observation, smart prevention, and natural control methods, you can protect your vegetables, fruit trees, and ornamentals while keeping your garden healthy, productive, and safe for pollinators and pets.

1. Aphids

Soft-bodied and clustered on new growth, aphids appear almost overnight during Florida’s spring and fall growing seasons. You will find them on tender shoots, buds, and the undersides of leaves, often in colors ranging from green to yellow, black, or even pink.

They suck plant sap and leave behind sticky honeydew that attracts ants and encourages sooty mold. In North Florida, aphid populations peak in early spring and late fall when temperatures stay mild.

Central and South Florida gardeners see aphids year-round, especially during dry spells when plants are stressed.

A strong spray from your garden hose knocks aphids off plants and disrupts their feeding. Ladybugs, lacewings, and parasitic wasps naturally control aphid numbers if you avoid broad-spectrum insecticides.

Planting nasturtiums, marigolds, and dill nearby attracts beneficial insects that feed on aphids.

University of Florida IFAS recommends monitoring plants weekly and using insecticidal soap or neem oil only when populations become heavy. Healthy plants grown in balanced soil resist aphid damage better than stressed or over-fertilized ones.

2. Whiteflies

Tiny white-winged insects flutter up in clouds when you brush against infested plants, settling back down moments later. Whiteflies gather on leaf undersides, where they feed on sap and lay eggs that hatch into scale-like nymphs.

Florida’s year-round warmth allows whiteflies to breed continuously, with populations often increasing rapidly during hot weather and periods of plant stress. They target tomatoes, peppers, squash, citrus, and hibiscus, weakening plants and spreading viral diseases.

South Florida sees the heaviest whitefly pressure, while North Florida experiences seasonal peaks in summer and early fall.

Yellow sticky traps placed near affected plants capture adult whiteflies and help you monitor population levels. Reflective mulches made from aluminum foil or silver plastic confuse and repel whiteflies from young transplants.

Encouraging natural predators like ladybugs, lacewings, and tiny parasitic wasps keeps whitefly numbers manageable.

UF IFAS suggests using horticultural oils or insecticidal soaps to smother nymphs and adults, applying sprays to leaf undersides early in the morning. Avoid over-fertilizing with nitrogen, which produces lush growth that attracts whiteflies and makes plants more vulnerable.

3. Spider Mites

Almost invisible to the naked eye, spider mites announce their presence through pale stippling on leaves and fine webbing between stems. These tiny arachnids thrive in hot, dry conditions, sucking chlorophyll from plant cells and leaving foliage looking dusty or bronze.

Florida’s dry spring months and summer heat waves create perfect conditions for spider mite outbreaks, especially on beans, tomatoes, citrus, and ornamentals.

Central and South Florida gardeners face mite pressure nearly year-round, while North Florida sees peaks during late spring and summer droughts.

Regular overhead watering helps temporarily reduce spider mite populations by washing mites off leaves and increasing humidity, though it does not eliminate infestations on its own.

Predatory mites, minute pirate bugs, and lacewings feed on spider mites naturally, so preserving these allies matters more than spraying.

UF IFAS recommends using a strong water spray to dislodge mites from leaf undersides, repeating every few days to break their reproductive cycle. Horticultural oils and insecticidal soaps smother mites without harming beneficial insects.

Planting garlic, onions, or chives nearby is sometimes suggested as a deterrent, but scientific evidence supporting this method is limited and inconsistent.

4. Caterpillars

Caterpillars chew ragged holes in leaves, sometimes stripping entire plants overnight. Florida hosts dozens of caterpillar species, from armyworms and cabbage loopers to tomato hornworms and saddleback caterpillars, each with different feeding habits and host plants.

You will notice their damage first, then find the caterpillars themselves hiding on leaf undersides or along stems.

South Florida’s tropical climate supports caterpillar activity year-round, while North Florida sees heaviest pressure in spring and fall when temperatures favor rapid growth.

Handpicking caterpillars works well in small gardens, especially early in the morning when caterpillars are sluggish. Bacillus thuringiensis, or Bt, is a naturally occurring soil bacterium that targets only caterpillars and remains safe for people, pets, and beneficial insects.

Apply Bt in late afternoon so caterpillars ingest it during their nighttime feeding.

Encouraging birds, wasps, and ground beetles helps control caterpillar populations naturally. Row covers protect young plants from egg-laying moths and butterflies.

UF IFAS emphasizes identifying caterpillar species before taking action, since some, like monarch and swallowtail larvae, deserve protection rather than removal.

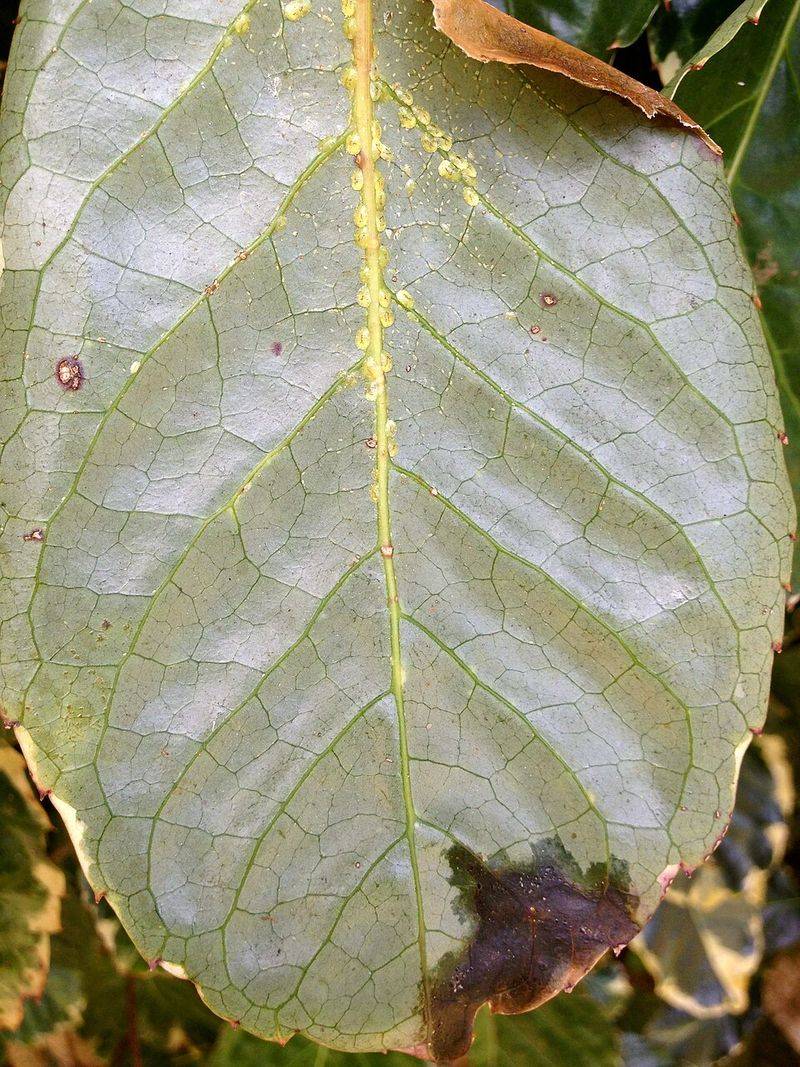

5. Leafminers

Winding white or tan trails snake across leaves, creating abstract patterns that reveal where tiny larvae tunnel between leaf surfaces. Leafminers rarely cause serious harm, but their damage looks unsightly and worries gardeners who notice it on vegetables, citrus, and ornamentals.

Adult leafminer flies lay eggs on leaves, and hatching larvae burrow inside, feeding on tissue while leaving the outer leaf layers intact.

Florida’s warm climate allows multiple generations per year, with activity peaking during spring and fall in North Florida and continuing year-round in South Florida.

Removing and composting affected leaves before larvae mature breaks the reproductive cycle and reduces future populations. Yellow sticky traps catch adult leafminer flies and help you monitor their activity.

Parasitic wasps naturally control leafminers by laying eggs inside the tunneling larvae, so avoiding broad-spectrum pesticides protects these helpful allies.

UF IFAS notes that healthy plants tolerate leafminer damage without significant yield loss, making intervention unnecessary in most cases. Floating row covers prevent adult flies from reaching plants during vulnerable growth stages.

Neem oil sprays may help deter adult leafminers from laying eggs, but they do not destroy larvae already feeding inside leaves.

6. Thrips

Slender and barely visible, thrips rasp plant tissue and suck the released sap, leaving behind silvery scars, distorted growth, and tiny black fecal spots. They attack flowers, buds, and young leaves, often spreading viral diseases as they move between plants.

Florida’s warm conditions favor thrips reproduction, with populations often building rapidly during spring and early summer, especially during dry weather.

Vegetables, citrus, ornamentals, and greenhouse plants all face thrips pressure, especially when rainfall stays scarce and humidity drops.

Blue or yellow sticky traps placed near plants capture adult thrips and help you assess population levels before damage becomes severe. Predatory mites, minute pirate bugs, and lacewings feed on thrips naturally, keeping numbers manageable when pesticide use stays minimal.

UF IFAS recommends overhead watering to wash thrips from plants and increase humidity, which slows their reproduction. Reflective mulches disorient thrips and reduce their ability to locate host plants.

Insecticidal soaps and horticultural oils smother thrips when applied thoroughly to flowers, buds, and leaf undersides. Removing weeds and plant debris around your garden eliminates thrips hiding spots and alternate hosts that support their populations between crops.

7. Scale Insects

Armored or soft-bodied bumps cling to stems, leaves, and fruit, looking more like part of the plant than living insects. Scale insects feed by inserting their mouthparts into plant tissue and sucking sap, weakening growth and causing leaves to yellow and drop.

They excrete honeydew that attracts ants and encourages black sooty mold, making plants look dirty and reducing photosynthesis.

Florida’s citrus, palms, ferns, and ornamental shrubs commonly host scale insects, with year-round activity in Central and South Florida and seasonal peaks in North Florida during spring and summer.

Scrubbing scale off plants with a soft brush or cloth dipped in soapy water removes many insects before populations explode. Horticultural oils smother scale at all life stages, including eggs hidden under the protective coverings.

Apply oils during cooler morning hours to avoid leaf burn.

Ladybugs, lacewings, and parasitic wasps naturally control scale populations, so protecting these beneficial insects matters more than immediate chemical intervention. UF IFAS suggests monitoring plants regularly and treating scale infestations early, before honeydew and sooty mold develop.

Pruning heavily infested branches improves airflow and removes concentrated scale colonies.

8. Chinch Bugs

Patches of yellowing, browning grass spread across your lawn during hot, dry weather, often mistaken for drought stress or fungal disease. Chinch bugs pierce grass blades with needle-like mouthparts, injecting toxins while they feed and causing turf to wilt and turn brown.

St. Augustine grass faces the heaviest chinch bug pressure in Florida, especially in sunny areas with thick thatch buildup. These tiny black and white insects thrive in hot, dry conditions, with populations peaking during late spring and summer across all regions of Florida.

Proper watering and mowing practices create conditions that discourage chinch bugs while favoring healthy grass recovery. Water deeply and less frequently to encourage deep root growth, and mow at the highest recommended height for your grass type to reduce stress.

UF IFAS recommends dethatching lawns when thatch exceeds half an inch, since chinch bugs hide and reproduce in thick thatch layers. Encouraging big-eyed bugs and spiders that prey on chinch bugs provides natural control without pesticides.

Insecticidal soaps and horticultural oils smother chinch bugs when applied to affected areas, though proper lawn care usually prevents serious infestations from developing in the first place.

9. Mole Crickets

Raised tunnels and loose soil across your lawn signal mole cricket activity below the surface. These burrowing insects damage grass roots as they tunnel, creating brown patches and uneven turf that feels spongy underfoot.

Mole crickets emerge at night to feed and mate, with activity peaking during spring and early summer when adults fly to new territories. South Florida sees year-round mole cricket activity, while Central and North Florida experience seasonal peaks tied to rainfall and soil temperature.

Beneficial nematodes applied to moist soil in late spring target young mole cricket nymphs, reducing populations before damage becomes widespread.

These microscopic roundworms enter mole cricket bodies and release bacteria that naturally control pest numbers without harming people, pets, or beneficial insects.

UF IFAS recommends applying nematodes when soil temperatures reach about 70°F and keeping soil moist for several days after application to help nematodes move through the soil.

Encouraging natural predators like birds and toads helps control mole cricket populations, though animals such as armadillos may cause additional lawn damage while foraging.

Avoid overwatering lawns during peak mole cricket activity, since moist soil attracts egg-laying females. Insecticidal baits formulated for mole crickets provide targeted control when populations become severe.

10. Snails And Slugs

Slime trails glisten across leaves, mulch, and walkways after rainy nights, marking the paths of snails and slugs that emerged to feed on tender plants. These mollusks rasp irregular holes in leaves, flowers, and fruits, often destroying seedlings and transplants overnight.

Florida’s humidity and frequent summer rains create ideal conditions for snails and slugs, with populations building during the wet season across all regions. They hide during the day under mulch, boards, pots, and leaf litter, emerging at night or on cloudy, damp days to feed.

Handpicking snails and slugs during early morning or evening patrols reduces populations quickly in small gardens. Copper tape or strips placed around raised beds and containers create barriers that snails and slugs avoid crossing.

Diatomaceous earth sprinkled around plants can damage the soft bodies of snails and slugs, but it loses effectiveness quickly when wet, making it less reliable during Florida’s rainy season.

UF IFAS suggests using iron phosphate baits, which remain safe for pets, wildlife, and beneficial insects while effectively controlling snails and slugs. Reducing mulch depth and clearing debris eliminates daytime hiding spots.

Encouraging ground beetles, toads, and birds that feed on snails and slugs provides natural control without baits or barriers.

11. Fire Ants

Mounds of loose soil appear across lawns, gardens, and pathways, each hiding thousands of aggressive fire ants ready to defend their colony. Disturbing a mound triggers mass attacks, with ants swarming up shoes and legs to deliver painful, burning stings.

Fire ants disrupt gardening activities, protect honeydew-producing pests like aphids and scale, and damage young plants by feeding on seeds and tender growth. South Florida’s tropical climate supports year-round fire ant activity, while Central and North Florida see reduced activity during cooler winter months.

Pouring boiling water directly onto fire ant mounds can destroy many ants without chemicals, but it often requires repeated applications over several days and does not always eliminate the entire colony.

UF IFAS recommends using bait products containing spinosad or abamectin, which foraging ants carry back to the colony and share with the queen. Apply baits when temperatures range between 70°F and 90°F and ants are actively foraging.

Encouraging birds and other natural predators may provide limited suppression of fire ant activity, though this method alone is not sufficient for reliable control. Maintaining healthy turf reduces bare soil where fire ants prefer to build mounds.