16 Old-School Vegetables Your Grandparents Loved (And You Should Too)

Before supermarkets and seed catalogs were filled with the same few veggies, your grandparents grew bold, flavorful, and often forgotten varieties right in their backyards.

These 16 old-school vegetables are packed with history, taste, and resilience—and they’re just waiting for a modern comeback in your garden (and your kitchen).

1. Salsify: The Oyster Plant

Long and slender with pale skin, salsify was once a staple in winter cooking. When cooked, this root vegetable develops a flavor reminiscent of oysters, earning its nickname.

Gardeners prized salsify for its ability to stay in the ground through freezing temperatures, providing fresh food when little else was available. Simply pull it as needed throughout winter months.

Growing salsify requires patience—it takes nearly 120 days to mature but rewards you with a versatile vegetable that can be roasted, mashed, or added to soups.

2. Cardoon: Artichoke’s Forgotten Cousin

Towering at four feet tall with silvery-blue foliage, cardoon makes a dramatic statement in any garden. Despite its striking appearance, few modern gardeners know this Mediterranean staple.

Related to artichokes, cardoon’s edible parts are the thick, celery-like stalks that must be blanched before harvest. Grandparents would wrap the stalks in paper or cloth for several weeks to reduce bitterness.

The flavor is nutty and artichoke-like, perfect for gratins or Italian holiday dishes. Plant cardoon where it can remain undisturbed, as it’s actually a perennial that returns year after year.

3. Scorzonera: Black Salsify

Nicknamed ‘vegetable oyster’ for its delicate flavor, scorzonera boasts striking black skin hiding creamy white flesh inside. Victorian gardeners cherished this root for its subtle sweetness and versatility in the kitchen.

Unlike many root vegetables, scorzonera doesn’t store well after harvest. Grandparents left it in the ground until needed, even through winter in most climates, creating a living pantry in their backyard.

Growing to about 8-10 inches long, these pencil-thin roots take nearly a year to mature. The patience required explains why fast-growing modern vegetables eventually pushed scorzonera aside.

4. Rutabaga: The Forgotten Winter Staple

Golden-fleshed rutabagas sustained families through harsh winters before refrigeration became common. Larger than turnips with a sweeter, nuttier taste, these root vegetables improve after light frost exposure.

Farm families stored rutabagas in root cellars by the bushel. The dense texture and rich flavor made them perfect for hearty stews and mashes that provided comfort during cold months.

Growing rutabagas requires little attention—plant seeds in mid-summer for fall harvest. Their natural resistance to pests and diseases made them reliable crops for gardeners who couldn’t risk crop failure when food security depended on successful harvests.

5. Good King Henry: The Perennial Spinach

Arrow-shaped leaves with a distinctive dusty sheen make Good King Henry instantly recognizable in heritage gardens. This perennial vegetable provided fresh greens for decades from a single planting, earning its place as a cottage garden staple.

Young shoots can be harvested in spring and prepared like asparagus. As the season progresses, tender leaves become the main harvest, offering a mineral-rich alternative to spinach that doesn’t bolt in summer heat.

Once established, Good King Henry requires almost no care while producing reliable harvests year after year. The plant’s remarkable durability made it essential for self-sufficient households before modern grocery stores existed.

6. Parsnips: The Forgotten Winter Sweet

Frost-kissed parsnips were winter’s natural candy before modern sweets became common. These cream-colored roots develop remarkable sweetness after cold exposure transforms their starches into sugar.

Colonial gardens featured parsnips prominently because they could remain in the ground all winter in most climates. Families simply dug them as needed, enjoying nature’s perfect storage system.

Growing parsnips requires patience—seeds germinate slowly and roots need months to develop. The reward comes in winter when other fresh vegetables are scarce, providing sweet, nutty flavor that outshines their carrot cousins in complexity.

7. Lovage: The Forgotten Herb-Vegetable

Towering up to six feet tall, lovage commands attention with its glossy celery-like leaves and hollow stems. This versatile perennial served triple duty in grandmother’s garden as herb, vegetable, and medicinal plant.

The leaves pack intense celery flavor that enhances soups and stews with just a small amount. Young stems can be blanched and eaten like celery, while seeds add distinctive flavor to bread and cheese dishes.

Once established, lovage returns reliably for decades with almost no care. A single plant provides more than enough for most families, explaining why our ancestors often planted it near kitchen doors for easy harvest.

8. Jerusalem Artichoke: Native American Staple

Sunflower relatives with underground treasures, Jerusalem artichokes produce knobby, sweet tubers that sustained Native Americans long before European contact. Despite the name, they’re neither from Jerusalem nor related to artichokes.

Grandparents valued these plants for incredible productivity—a handful of tubers can multiply into bushels of food. The crisp, sweet tubers taste like water chestnuts when raw and develop nutty flavors when cooked.

Growing Jerusalem artichokes requires almost no effort. Plant tubers in spring, then stand back and watch them reach for the sky, producing cheerful yellow flowers before harvest in fall.

9. Hamburg Parsley: The Root Parsley

Hamburg parsley looks ordinary above ground with typical parsley foliage, but beneath hides a secret—large white roots resembling small parsnips. These forgotten vegetables were kitchen standards before modern carrots dominated gardens.

The roots offer a flavor that combines parsley’s herbaceous notes with earthy parsnip undertones. Grandmothers used them to enrich winter soups and stews when fresh herbs were unavailable.

Growing Hamburg parsley follows the same pattern as regular parsley but requires deeper soil for proper root development. The plants are biennial, producing larger roots in their second year—a patience modern gardening has largely forgotten.

10. Orach: Mountain Spinach

Vibrant purple-red leaves make orach one of the most beautiful forgotten vegetables. Also called mountain spinach, this heat-tolerant green continued producing when regular spinach surrendered to summer temperatures.

Grandmothers treasured orach for its mild flavor and colorful contribution to summer meals. The purple pigments even transfer to pickling brines, creating naturally colored preserved foods.

Growing orach couldn’t be simpler—seeds sprout quickly and plants reach harvesting size in just weeks. Unlike modern spinach, orach self-seeds readily, returning year after year once established in the garden.

11. Turnip-Rooted Chervil: The Forgotten Aromatic

Delicate fern-like foliage above ground gives no hint of the aromatic treasure beneath—gray-brown roots with distinctive anise-myrrh flavor. This forgotten vegetable was once a staple in European noble kitchens.

The roots develop their best flavor after exposure to frost, making them perfect winter vegetables. Grandparents would leave them in the ground until needed, harvesting fresh even in January in milder climates.

Growing turnip-rooted chervil requires unusual timing—seeds need fall planting and cold stratification to germinate in spring. This complex growing pattern explains why this aristocrat of root vegetables gradually disappeared from common gardens.

12. Malabar Spinach: The Summer Green

Vines trailing with glossy, deep green leaves, Malabar spinach brought reliable greens through summer heat when true spinach failed. Despite its name, this tropical plant isn’t related to spinach but offers similar nutritional benefits.

Grandparents in warmer regions valued Malabar spinach for its incredible productivity during the hottest months. A single plant can produce bushels of tender leaves from summer through fall frost.

Growing Malabar spinach requires warm soil and something to climb—a trellis or fence works perfectly. The beautiful vines with purple stems add ornamental value while providing nutritious greens that hold up better in cooking than regular spinach.

13. Celeriac: The Gnarly Flavor Powerhouse

Beneath its rough, knobby exterior, celeriac hides creamy white flesh with intense celery flavor. This ugly duckling vegetable was a winter kitchen staple before refrigeration made fresh celery available year-round.

Farm families prized celeriac for its exceptional storage ability—properly harvested roots last months in cool storage. The concentrated flavor made it perfect for adding depth to winter soups and stews.

Growing celeriac requires patience and consistent moisture. Seeds must be started early indoors, and the developing roots need regular watering to develop properly. The extra effort explains why many gardeners eventually abandoned this flavor-packed vegetable.

14. Sea Kale: The Coastal Delicacy

Wavy blue-green leaves that shrug off salt spray made sea kale a favorite in coastal gardens. This perennial vegetable produces multiple harvests—blanched spring shoots, summer leaves, and even edible flowers.

Victorian gardeners prized sea kale so highly that wild populations were threatened by overharvesting. They grew it in gardens, covering emerging spring shoots with pots to blanch them white and tender.

Growing sea kale requires patience initially, but plants live for decades once established. The striking appearance makes it suitable for ornamental gardens too—wavy silver-blue foliage and honey-scented white flowers attract beneficial insects.

15. Skirret: The Forgotten Sweet Root

Medieval gardens weren’t complete without skirret, a sweet root vegetable that was Europe’s main sugar source before cane sugar became widely available. The plant produces clusters of slim white roots that taste like a blend of carrot and parsnip with honey notes.

Grandparents valued skirret for its perennial nature—once planted, it returns year after year with minimal effort. Each plant produces multiple finger-sized roots that can be harvested selectively without disturbing the whole plant.

Growing only about two feet tall with delicate white flowers, skirret fits easily into modern gardens. The roots can be eaten raw, roasted, or added to stews for natural sweetness.

16. Egyptian Walking Onion: The Self-Planting Allium

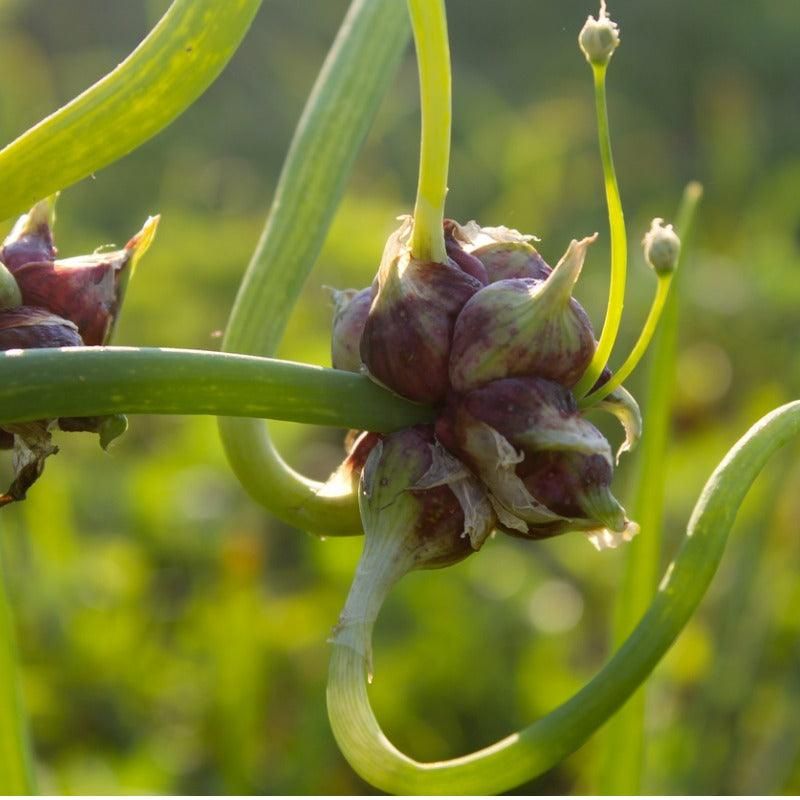

Curious topsets forming where flowers should be give Egyptian walking onions their name. These bulblets grow heavy, bend the stalk to the ground, and root themselves—literally ‘walking’ across the garden over years.

Grandparents valued these perennial onions for providing three distinct harvests: green onion-like shoots in spring, small bulbs in summer, and topsets for replanting or eating in fall. No part went to waste in frugal farm kitchens.

Growing Egyptian walking onions requires almost no effort—plant once and harvest for years. Their reliability and self-propagating nature made them essential in gardens where saving seed and ensuring food security were daily concerns.